Editorial Note: This an unexpected eighth part to the Lasagna Trilogy that started with Not So Bad Pharma and runs through to Witty A: Report to the President.

Ondine

Ondine was a nymph whose lover swore that his every waking breath was a testimony to his love of her. Finding him unfaithful, she cursed him – should he fall asleep he would stop breathing.

Marilyn died of an overdose of barbiturate sleeping pills (Tragedy). A bystander, Lou Lasagna, noted she had been denied access to a sleeping pill that was safe in overdose, the first pill of any sort that had been proven to work and be safe in an RCT before it was marketed. She was denied by doctors who put more weight on uncontrolled clinical observations than RCT data. As she died, she uttered a curse. Life went on. At first Lou noticed nothing but over the years his horror grew (Empire 1, Empire 2).

Fishers

In the Spring of 1926, Ronald Aylmer Fisher, a lifelong smoker and denier of the idea that smoking might cause lung cancer, undertook some studies on the effects of fertilizers on seed growth in some fields outside Cambridge. Many factors could confound the results of a fertilizer study from differences in soil drainage, to the angle of the incident sunlight, exposure to wind and a myriad of soil elements that could only be guessed at. Fisher hit on a way to control both known and unknown confounders – he randomized the fertilizer to alternate seed and soil patches. And so the randomized controlled trial (RCT) was borne.

Fisher tied significance testing to RCTs. If we got the same result every time, we had designed a good experiment. There was a Quod Erat Demonstrandum quality to this – shave a bit off one side of a coin and you can expect heads to come up nineteen times out of twenty. He was looking for something close to a Euclidean Theorem – if you understand something the results will almost always be the same. But this insight on what Fisher meant by statistical significance, like most things about RCTs, has been inverted or perverted.

In 1947, Bradford Hill applied Fisher’s randomization to testing whether claims made for the efficacy of streptomycin for tuberculosis held up. He didn’t discover that streptomycin worked – others had done that in laboratories and clinics. But against a background of desperation and false claims, he showed that this time the claims could not be dismissed.

The RCT tide came in quickly after that and by the mid-1960s Hill noted that drug company salesmen ironically were encouraging doctors to use our products based on RCT evidence. While believing RCTs had a place in medicine, Hill noted that if RCTs ever became the only way to evaluate drugs that the pendulum would not just have swung too far it would have come off its hook.

Pharmers

RCTs have since been fetishized – made into a Golden Calf. Few can see any problems with bringing the rating scales and other measuring tools linked to them into clinical care – to make it more scientific. But just as with Midas, the touch of Gold brings death not benefit.

The pendulum has not just come off its hook, Pharma has picked it up and is battering people and governments over the head with it. We have recently had the close to degrading spectacle of the UK government in a parliamentary committee touting for Pharma “clinical trial business” and being told by GSK and Roche that UK clinical practices are just not Pharma friendly enough.

In this battering of people and governments, Pharma’s most useful allies are the proponents of Evidence Based Medicine, who insist clinical trials are if not the only way forward then by far the most useful way. RCTs, they indicate, would be just perfect if trial design was taken out of Pharma’s hands, if we had a registry of all trials done, and if we were let have a Witty-style peek at the data from time to time. It’s this fetishing of trials by independent academics that gives Pharma its grip over US and European governments.

Mediculture or medicine?

For 80 years we have unthinkingly celebrated Fisher’s apparent managing of confounders. Many trumpet the ability of RCTs to demonstrate cause and effect. Few accept that these trials are simply association studies with a particular method for controlling confounders. Few guess that there are more disturbing problems.

Let’s return to whatever image an agricultural field outside Cambridge conjures up in your mind. Using her FishCam, Crusoe watched Fisher weed his patches of Rye, exclude all stones, meticulously ensure each of the A patches was the same size as the B patches and got the same amount of seed. After days of preparation, he allocated the fertilizer randomly and headed home to his pipe. (For more on Crusoe see The Girl who was not Heard). She saw him check the patches weekly and then on the night of June 1, just as the first plants were sprouting, she saw a Sprite arrive and sprinkle Pixie Dust on Fisher’s handiwork.

Some weeks later when there was clearly much more Rye growing on the A than on the B patches, and the Rye on B was moldy, she saw Fisher race out to invest in Company A shares.

Using her Sprite tracking App, Crusoe locates where the imp dwells and while he is out one night creating mischief, she sneaks into his tree-house, finds the bag containing the Pixie Dust, steals some and brings it home to analyse. And for good measure she borrows a pretty pink envelope lying beside it.

The Dust contains a mixture of MM Rye and MM mold. She opens the envelope and finds a message: If you chant these words on scattering the supercharged Rye will all land on the A patches and the mold on B:

‘Norma-Jeanne thou art, Marilyn thou wilt be, and Queen of Camelot hereafter’.

Crusoe concludes that this can never happen in agriculture and there is no need to warn Fisher he’s at risk of losing his money. But she sees that this can and must happen in medicine, and that it won’t be spotted because medicine is a much more desperate business than agriculture. Human beings and diseases are not an inert field that you sprinkle fertilizer on. In medicine you give poisons that have effects on both a person and a disease that no randomization can control for.

She concludes that RCTs will be of limited use for testing medical treatments but she recognizes that the idea of a simple solution has irresistible appeal to desperate people and the invention of this idea makes investment in pharmaceutical companies worthwhile – because it hands companies the perfect way to market Snake Oil.

Standing back and surveying the clinical domain over seven decades she sees the value of RCTs as a marketing tool for pharmaceutical companies steadily grow until it far outweighs the value of trials to doctors testing treatments in clinical conditions. As this happens she notices one group of clinicians – those with least contact with the pharmaceutical industry – develop a delusional belief in the invincibility of RCTs.

These believers try to update GSK Chesterton’s (and Gandhi’s) message that it is not Christianity that has failed, it is Christians, substituting RCTs for Christianity. She sees the annual Christmas solemnities of a people celebrating their control of confounders, and giving thanks to EBM, completely oblivious to the confounding produced by the Clinical Sprite that cannot be overcome.

The clinical sprite

Imipramine, the first antidepressant, was discovered in 1957, the year Fisher left England for Adelaide. It was launched in 1958 – not an RCT in sight. A year later in 1959, three years before Fisher died of cancer, and a few miles away from his patches of ground, a meeting of psychiatrists was convened in Cambridge to discuss its effects.

At this meeting, some doctors, mainly Danes, noted on the basis of the Christmas Tree lightbulb test that wonderful though it was for many of their patients imipramine could trigger suicidal and homicidal ideation in some (See Time to Abandon Evidence Based Medicine at 38 minutes et seq).

When Christmas Trees had old style light bulbs, after a year laid up there was an annual drama as the lights failed to work. Unscrewing them sequentially would finally lead to one which when unscrewed lit them up. Screwing that bulb back in turned them off again. Jettisoning this bulb fixed the problem, even more conclusively than Fishers nineteen heads out of twenty.

So imipramine causes suicide. But it is also a far more potent antidepressant than Prozac, or any subsequent antidepressant. It got people with melancholia well where later drugs don’t. Melancholic patients are 80 times more likely to commit suicide than mildly depressed patients – according to studies drug companies cite.

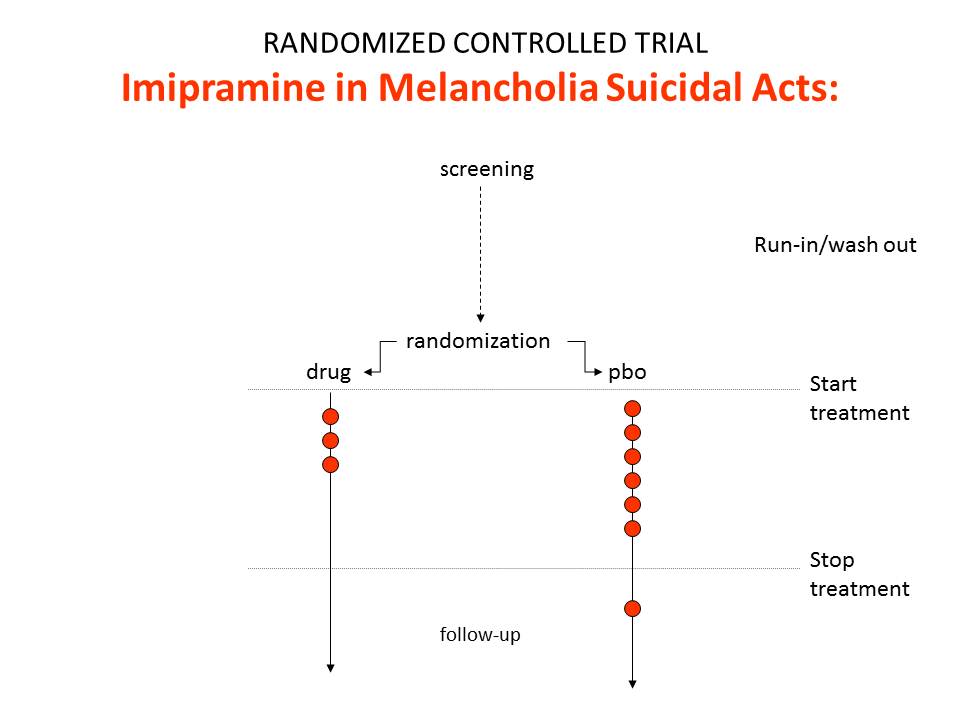

Accordingly comparing imipramine and placebo in an RCT would likely show less suicides and suicidal acts on imipramine than placebo. The relative risk might be 0.5. Imipramine protects against suicide.

Had an RCT been done showing no risk on imipramine, we cannot know for sure what effect it might have had on the doctors in Cambridge, celebrating imipramine’s benefits but acutely aware of its hazards.

But some hints come from an RCT four years earlier, in 1955, which found reserpine worked well for depression and caused no suicidality. The immediately preceding articles in the Lancet were Christmas Tree light bulb reports of it causing suicide from Geelong and Dunedin. Where? The field didn’t need an RCT to know that reserpine could be useful. In the face of an RCT from the most distinguished Institute in the world showing no problems, doctors still had no difficulty believing reserpine could cause suicide on the basis of light bulb reports from goodness only knew where. If asked what they made of these new-fangled RCTs, most clinicians would almost certainly have said “interesting but hardly clinically relevant”.

It took a political impasse about drug regulation in 1962 and the need to find something simple enough for bureaucrats to work with to produce the primacy that RCTs have now. Something signed into law by Marilyn’s lover, nine weeks after her death and ten weeks after Fisher’s, that put the lights out on the Christmas tree.

The sprite’s RCT

The findings of our imipramine thought experiment are represented in figure 1. These are the findings even though the drug causes suicide.

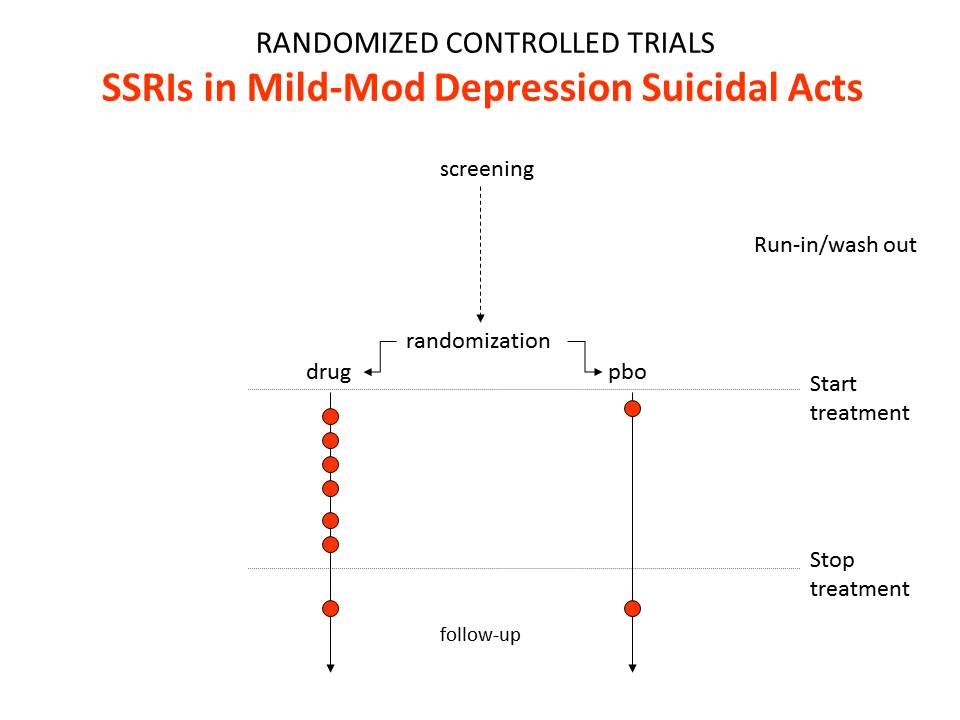

Figure 2 shows the findings for suicides and suicidal acts in SSRI trials.

In these trials we get a relative risk that the drugs will cause suicide and suicidal acts of 2.0. This happens because SSRIs are much weaker than imipramine and so were tested in people who were mildly depressed at little or no risk of suicide. When the findings got to be statistically significant, the regulators seemingly felt obliged to agree that the SSRIs caused suicide and came out with a warning to that effect.

The regulators were wrong. The data in this SSRI population show the drugs produce an excess of suicides over lives saved. They say nothing about causality except in so far as there could not be an excess of suicides if the drugs didn’t cause suicide. In the case of the SSRIs and suicide, the evidence comes from Teicher’s 1990 Christmas Tree light bulb paper on Prozac and suicide – and earlier cases.

The first point to make is this is not confounding by indication.

The second is that despite mantras to the contrary, RCTs do not and cannot show cause and effect.

The third is that they do not even give useful data on frequency. We in principle cannot have any idea from RCT figures how often antidepressants trigger suicidality.

But here’s the real deal. This finding is not an inconvenience that stems from some oddity to do with antidepressants or suicide or drug companies. It is intrinsic to RCTs within medicine. It can be expected every time a treatment and an illness produce at least superficially similar outcomes – whether a benefit or a harm.

It happens to cardiac rhythm problems in trials of anti-arrhythmics given for cardiac arrhythmias, and to breathing difficulties in trials of anti-asthmatics given for asthma. It happens with vaccines. It happens to the benefits of treatments just as much as their harms.

It holds as true for completely independent RCTs with hard outcome measures, no surrogate outcomes, complete data access, and intention-to-treat analyses, in long duration or short duration studies, as it does for industry studies.

It means that notions of Numbers Needed to Treat (NNTs) or to Harm (NNH) or even treatment effect sizes are for the most part little more than empty statistical artefacts, except in so far as they apply to dead bodies.

Patients can in fact distinguish between depression induced and drug induced suicidality or between antidepressant induced and spontaneous recovery from depression – if we ask them. Patients can tell you if a drug is ‘working’ even if its not ‘working’ – as when they say this SSRI is producing a useful emotional numbing even though it’s not making much difference overall. It is only if you listen to the patient that you can know whether to add another Therapeutic Principle into the mix or whether you should stop the drug they are on and try another.

Having your ears stopped to what the patient says, with the poison of “this is anecdotal data”, is a way to turn your patients into ghosts who must wander abroad seeking someone to come to their aid.

Cardiologists can also distinguish between drug and illness induced arrhythmias.

But if we believe a patient’s answers or a cardiologist’s clinical experience, RCTs immediately shape shift from gold standard evaluation to gold-plated but often misleading association studies.

So, who does not asking patients suit most?

The only trials that the Clinical Sprite cannot confound are Drug Trials. These trials of a drug done in healthy volunteers reveal unconfounded drugs effects. But there is no register of these trials, and no access to their data even though there are no issues of clinical confidentiality involved.

The clinical pixie

The Clinical Sprite has a sister – the Clinical Pixie.

In the late 1980s, Eli Lilly undertook a trial of Prozac in a group of patients with recurrent brief depressive disorder (RBDD). In this trial placebo was sweepingly statistically superior to Prozac. The study was published four years later shorn of all key data.

In the early 1990s, SmithKline Beecham (GSK 2B) undertook study 106 of Paxil – Prozac’s sister SSRI in the same hospital centre, in the same RBDD patients, possibly with some of the same patients who had been in the Prozac trial. This second study terminated early. The results were never published. The rate of suicidal acts on Paxil (Paroxetine) was three-fold higher than on placebo.

Nevertheless a few years later GSK 2B undertook study 057 in a similar group of patients. Several different sets of results from this trial circulate, none of which support using Paxil in this group of patients.

In April 2006, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK Not 2B) issued a press release with the following figures for suicidal acts in the Paroxetine trials in Major Depressive Disorder.

Suicidal Acts in MDD Trials

| Paroxetine | Placebo | Relative Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal Acts/ MDD Patients | 11/ 2943 | 0/ 1671 | Inf (1.3, inf) |

The MDD patients show a significant increase in the suicidal act risk on Paroxetine. But even though the results of studies 106 and 057 were so bad, GSK Not 2B gleefully added them in to the mix – and when they did so Hey Presto the risk from Paxil vanished. It can even be made protective against suicidal acts (See Table 2).

Suicidal Acts in MDD & RBDD Trials

| Paroxetine | Placebo | Relative Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal Acts/ MDD Patients | 11/ 2943 | 0/ 1671 | Inf (1.3, Inf) |

| Suicidal Acts/ RBDD Patients | 32/ 147 | 35/ 151 | 0.9 |

| Suicidal Acts/ MDD & RBDD Patients | 43/ 3090 | 35/ 1822 | 0.7 |

We can dump lots more suicidal acts into the RBDD trials and still get the same magical outcome – see Table 3.

Suicidal Acts in MDD & RBDD Trials w Sprite

| Paroxetine | Placebo | Relative Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal Acts/ MDD Patients | 11/ 2943 | 0/ 1671 | Inf (1.3, Inf) |

| Suicidal Acts/ RBDD Patients | 48/ 147 | 35/ 151 | 1.4 |

| Suicidal Acts/ MDD & RBDD Patients | 59/ 3090 | 35/ 1822 | 0.99 |

This paradoxical outcome is not a funny quirk of antidepressants and suicide. It is totally predictable and obvious. I could have advised GSK-2B or Not 2B to do studies 106 and 057 to get this outcome. Knowing what a drug can do, you can often design studies that use a problem the drug causes to hide that very same problem.

Now the pillars of the EBM establishment, so used to dealing with the scurvy knaves from Pharma, look at this and say it is just bad meta-analytic technique – you shouldn’t mix studies like this. And you shouldn’t. There is a horrific scandal here – FDA, MHRA, and the luminaries of EBM have let GSK Not 2B get away with this without a peep of protest.

But there is a deeper problem. We can see what is going on here. But exactly the same thing can happen by accident in clinical trials done in every illness we don’t fully understand – from pain to Parkinson’s Disease.

RBDD patients can meet criteria for MDD easily. Provided there is more than one of them entered into MDD trials randomization will ensure these Pixie patients will hide some benefit or harm.

Unlike fertilizers, drugs have a hundred or more effects. When we Design an Experiment employing randomization to manage the unknown unknowns for one of these effects, we risk generating an ignorance about ignorance regarding most of what the drug in fact does, and sometimes even for the effect we are focused on. This is true for statins, antibiotics and all drugs – not just antidepressants.

Pharmagnosia

Generating ignorance about ignorance is a serious clinical problem – for which pharmagnosia seems a good term. If a good medicine is a chemical that comes with good information, then RCTs through pharmagnosia are leading to a systematic degradation of our medical arsenal.

All RCTs do harm. Some do good as well. Pharmagnosia is worth risking when there are grounds to think a claimed benefit does not hold water and if wrong vulnerable patients are likely to be harmed. If the drug doesn’t work, we don’t CReate Ignorance in MEdicine (CRIME).

The only way to get the result Fisher would have insisted on for the main effect of a drug rather than a fertilizer, that is the same outcome every time, is to understand the clinical condition you are treating and the agent you are using so that you produce a Quod Erat Demonstrandum – this treatment works every time or no it doesn’t work.

But if we understand the clinical population this well, RCTs come close to being irrelevant to moving decent medicine forward. Their main value lies in dealing with the claims of hucksters and charlatans.

The Clinical Pixie looks like Tinker-belle but she is a not a benign fairy. There are far more MDD patients that RBDD patients in this world. If you spot what she has done in this case, you can see that the results show the drug harms more people than not.

But if you don’t spot what she has done, she will beguile you if you are a public health official or regulator into supporting a treatment in front of the press saying it has a favorable risk benefit ratio by which you mean produces more benefit than harms on a population basis. You will do this although in fact the treatment is cripplingly bad for far more patients than it benefits.

At a rough guess, 90% of these pronouncements by regulators are wrong and 99% or more are lacking in appropriate supportive evidence.

One of the most egregious examples of this came recently in a Cochrane review of Statins that focusing exclusively on their lipid lowering effects, neglecting their effects on muscle, endocrine and cognitive function, concluded that the evidence supports their use (Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 1). Only time will tell which of the current blockbuster drugs will in the longer run take the title for the drug group that has caused the most damage but the statins are worth betting on.

In Elsinore

Within the walls of the Elsinore, the citizens of EBM remain at ease. As far as they can see the only Sprites that might confound clinical trial results are those scurvy knaves who work in the pharmaceutical industry. The citizens still believe that the suicide risks of antidepressants were discovered in clinical trials done in children, not knowing that trials were actively and likely deliberately used to hide an obvious link for fifteen years.

Within the Citadel, Claudius has decreed that anyone who seems to question the primacy of trials should never be engaged in public, can be attacked in ad hominem fashion, or failing all else should be consigned to the Antidepressants & Suicide Chamber, on the door of which there is a notice Here be Sprites.

Lethe, the river of forgetfulness runs through EBM. What need is there for History. Things could not have been better in the past. Fisher’s texts are revered as they lie sealed in a glass cabinet. No-one can find out that he was looking for a Christmas Tree light bulb equivalent. They don’t even know he was dealing with agriculture not medicine.

In the Real World, outside the Castle, the one foot on the ground world, RCTs can be seen to function in medicine primarily as a rhetorical device giving the impression that if a drug has passed through them, a patient will get the same beneficial outcome time after time, even when in fact in 80% of the trials the drug has performed worse than placebo.

Cut to the battlements of Elsinore, where a man stands paralyzed with fear by the approach of what his fevered imagination sees as a ghost. The ghost of a beautiful woman. Frozen with fear, he murmurs:

Let us go in together

And still your fingers on your lips, I pray

The time is out of joint, Oh Cursed Sprite

That ever I was born to set it right.

Inside, Crusoe takes off her white cloak.

“Dr Gøtzsche I presume.

I’m thrilled you mistook me for Marilyn but her ghost walks elsewhere. It was the children crippled by thalidomide that led her to suicide. Another MM, Morton Mintz, broke the story in the US just three weeks before she overdosed. No, I’m here because Denmark is close to the worst place in the world for patients. Their ghosts seek rest. More SSRIs have come from here than anywhere else. We need to hoist the malignant Sprite responsible for this with his own petard.

Your trip to England with Rosendorous and Guildenacre, two good people, to demand access to clinical trial data could go badly wrong. More than anyone else, through your work on breast screening you have shown that good intentions do not prevent disasters. But if your wonderful efforts to get access to RCT data makes it seem that RCT’s are important rather than that the withholding of even cruddy data is a scandal, you just could make things much worse”.

Illustration: Put-Me-to-Sleep Pills, © 2013 created by Billiam James

Dear Dr. Healy,

Interesting post. It appears to me, if I am not misunderstanding your point, that you are arguing against RCTs based on our inability to differentiate between medication adverse effects vs. under-treatment of underlying illness when the observed outcomes are similar.

However, our drug development system starts with Phase 1 experiments with normal patients to establish safety threshold of dosages for investigational new drugs. As you briefly alluded to in your argument, one can only see adverse events in this group of individuals because there is no “efficacy” to speak of in normal people. Phase 2 trials establish dose response and appropriate dosing that provides the greatest efficacy, which is then carried out Phase 3 trials. Perhaps we are too fixated on Phase 3 studies while ignoring Phases 1 and 2, but if these earlier phases were carried out properly, there is no reason to believe why Phase 3 results will be unreliable. We need to respect the Bradford Hill criterion of dose response. Differentiating between adverse event vs lack of efficacy (due to inadequate dosage) when they produce the same outcome can be solved by increasing the dose (assuming we begin at the minimum effective dose) and evaluating the dose-response curve. If there is a true adverse event, with increase in dosage one sees a persistence or worsening of outcome (aka adverse effect). If there is lack of efficacy due to inadequate dosage, with increased dosage one will see improvement in outcome when you increase the dose.

At any rate, the Christmas light doesn’t solve the issue – for example, if one stops an SSRI in a patient and they commit a self-harming act, there is no way to differentiate whether the act was due to residual adverse profile of the drug, the patient convincing themselves that they feel worse because of the placebo effect, or a relapse of depressive episode.

I am not sure what the tables on paroxetine and suicide are trying to illustrate – we all know that absolute risk differences provide more objectivity than RRs, and it is rather disappointing to see this not reported in the tables. Once this has been incorporated, it will become clear that the suicidal effect crossed to paroxetine’s favour because the placebo group had a higher suicide rate than paroxetine in the RBDD trial in Table 2, in contrary to the MDD trial. Further, the absolute risk difference of RBDD trial (in favor of paroxetine) was larger (1.4%) than the MDD trial (in favour of placebo, 0.37%), so the results are not surprising. Yes, it is possible to “dilute” the absolute difference between two groups by adding to both numerators and denominators in both groups, but you also lose statistical precision – I am not sure why it is provided only for the first column and not the rest – they are likely non-significant. If that is the case (where an intervention arm is not proven superior to a placebo), I don’t see how a new investigational drug will be approved. At any rate, if one attempted to combine different patient populations into a single trial, one would be able to see this in Table 1 and cringe.

Your article does not allow for a genuine dialogue on EBM by unnecessarily debasing RCTs, pointing out their roots in agriculture as if nothing from that industry can be trusted; well, I consider it fortunate that their origins did not involve Christmas lights.

Yan

Many thanks for taking the time to read and comment. First, almost no independent investigators run healthy volunteer studies – which are perhaps the only trials that should be called drug trials. The phase 1 studies industry do remain unregistered with total lack of access to the data from them even though there are no issues of confidentiality. The events that happen in condition trials are not collected systematically in part because the primary outcome of a condition RCT is the benefit and its not possible to capture all events in detail – but also companies to some extent know what other events may be happening and should be downplayed. This leads to a poor recording of the vast majority of events that happen on treatment. Companies also get away with claiming that these events are not statistically significant and hence didn’t happen when they should not be able to apply statistical significance testing to such data and any increase in the number of events should be regarded as a true increase until proven otherwise.

The findings here don’t depend on a use of relative versus absolute risk. They hinge on a poor understanding of the clinical conditions being treated so that the patients entered into trial are highly likely to be heterogeneous. Where randomization can in some cases help us manage clinical complexity, in a number of instances it can do the opposite and the point behing Tables 1-3 is to show how easily this could happen in practice making it almost inevitable that it does happen to some extent.

Re Christmas tree light bulbs (CTLBs), this is not set up as infallible. The argument is that RCTs are not infallible either and in many instances are less helpful than CTLBs. In fact the antidepressant and suicide story is all about how companies were able to convince academia the media, the proponents of EBM and everyone else that shoddy RCT data on antidepressants and suicide trumped convincing CTLB reports.

In terms of the issue you mention though a CTLB approach does better than you seem to think – in that one of the options for suicidal acts on stopping treatment is dependence on the drug being stopped and withdrawal suicidal acts. If the agitation clears quickly on reinstating the drug this is most likely to be dependence and withdrawal related. The CTLB works well here.

We are not talking about rare events. The agitation/anxiety that results in suicidal acts on antidepressants occurs in up to 20% of patients put on them. Over half the people put on antidepressants will have significant withdrawal problems when stopping.

Its easy to blame pharmaceutical companies for all that is wrong in clinical practice. We really should also scrutinize our own instruments and practices. We need to ask whether just like screening RCTs have the potential to cause more harm than good. I think the post shows how this could happen. This doesn’t mean RCTs don’t have a place.

A second point is this. Where exactly have the advocates of EBM and RCTs been when it comes to the issues of adverse events? None have been involved in the antidepressants and suicide story, or the adverse effects of statins story.

But maybe there is one point of agreement. I think RCTs are useful (not infallible) when they show a drug hasn’t got a claimed benefit. In this case the onus is where it should be – on companies to find some patient group who may benefit. In practice because we fail to recognize the limitations of RCTs we have a world where patients are injured because of RCTs and the onus is on them to prove the drug caused it, and in this context the voluntary efforts of others to do something good for their fellow citizens becomes the means by which patients injuries go unrecognized and unaddressed.

David

Sorry – two last points after watching your Nov 2012 talk at Cardiff:

1. I feel the need to reiterate that RCTs as they are currently designed do not have the power to detect rare adverse events – this has been conclusively shown: http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001407. Again, detecting the rare adverse events is best done in the post-marketing pharmaco-surveillance, unless we are willing to accept a system whereby we randomize at least 100,000 people for 5 years for each drug before it is considered for approval.

2. When the condition that the drug prevents and its alleged adverse events result in the same outcome, one either needs to look in normal controls (as per my comment above), or one clearly needs to look at the composite of the two. Going to your imipramine example, it is illogical to conclude that imipramine causes suicides when it prevented more suicides than the ones it “caused”. One can just as forcefully argue that depression’s adverse effect is suicide.

By your logic, I can say that warfarin causes ischemic strokes because patients with atrial fibrillation who are on warfarin have ischemic strokes – no, warfarin PREVENTS strokes, but not every one. Not treating patients with warfarin also causes strokes. The only way do prove warfarin’s efficacy, indeed, is through a placebo-controlled study. Similarly, when imipramine prevents more suicide than the ones it supposed “causes”, then it is an anti-suicidal agent by definition.

Yan

We are not talking about rare adverse events, we are talking about events that happen in up to one in every five people taking these drugs. These events happen in healthy volunteers as well as depressed patients.

Maybe I failed to make the imipramine point fully clear. Put imipramine into the populations SSRIs were trialled in and it too will show a doubling of the rate of suicidal acts compared to placebo. I can construct trials of imipramine to give relative risks varying from 0.5 to 6.0.

David

I’m imagining a worried parent taking her six-year-old son home from yet another trip to the emergency room. She believes she knows what the problem is: strawberries. Every time he eats them, he breaks out in a rash and his face and hands swell. Never happens otherwise. This time, after the class trip to the U-Pick Berry Farm, his throat swelled up too. My god, he could have died! She’s taking him back to that wretched “Evidence-Based HMO” and telling them what’s what.

But the doctor still won’t provide a “no strawberries” note for the child’s school. Worse yet, he tells the mother, “As long as there is even a six percent chance that you’re wrong, I want you to keep feeding him strawberries. They are a very good food, full of vitamins and absolutely fat-free. I have many children in this practice who might be living on chocolate milk and Cheez Doodles if it weren’t for strawberries. They won’t eat apples, you know. Listen, these problems are not as rare in children as you might think. I had another boy in here last week in the same condition. And you know what the dad thought the problem was? Peanut butter. I kid you not. Parents have all these interesting theories, but they’re just anecdotes.”

“Most likely your son has a chemical imbalance – his histamines just run unnaturally high. Luckily, there’s some really powerful medications we can put him on. If he takes them for the rest of his life, he will be able to live almost like a normal child. And we can always add a stimulant if he gets too sleepy on the meds.”

Maybe the only reason this hasn’t come to pass is that GSK doesn’t have a patent (yet) on strawberries or eanut butter? Give them time. They have a patented prescription-only fish oil called Lovaza, and it’ll only set you back about $200 a month …

Thanks for helping us see the madness.

Heally, do you have any information on whether or not the general public is catching on to how drug companies operate in such a shady way? I know many people know this, but I’m wondering if this knowledge is being learned by more and more as time goes on?

What I’ve seen for the most part on the forums I go on is that many of them think severe, permanent effects of psychiatric drugs are only slightly less rare than seeing a unicorn. I know this because I will tell how these meds have affected me, and they tell me I must be mistaken. They say this is next to impossible. I ask why they feel so strongly about their idea of it being next to impossible and I get the same reaction every time. They say “well it hasn’t affected me like that”. I guess their logic is something like, “well, its not raining where I’m at so it must not be raining anywhere else.” I ask for them to share facts behind their ideas and they either point to a sensational article about antidepressants or they just say “its common sense.”

They’re so mislead.