In Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder on RxISK, I mention that for me a key paper in a reference list of 27 references was one by Ann Bauer and colleagues, who recognized limitations to the epidemiological data but nailed their colours to the mast in saying that there was sufficient evidence here that pregnant women should be warned of a possible link between acetaminophen – paracetamol and neurodevelopmental delay.

In the post, the approach Bauer and colleagues took was contrasted with a GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) approach that dug deep into technical details and had multiple procedures that appear designed to give an appearance of objectivity. When challenged on key points, the GSK spokesman said, as many in the industry say, that he and the process in place was not in the business of coming to value judgements. Their task was to amass evidence.

This choice of words is wonderful. Getting involved in values sounds like being sucked into something religious rather than sticking to science and of course we want our scientists to stick to the science.

Value Judgements

Many colleagues whose work I admire and company I enjoy seem to see things is a similar way to the GSK dude cited here. They aren’t keen to get involved in issues I take positions on. This ‘attitude’ is most apparent when it comes to possible involvement as an expert in a legal action. Their body language, and tone of voice, suggest they see this as muddying their scientific hands.

Being a legal expert, even on the side of patients injured by drugs, is as bad a conflict of interest problem for many of the ‘good’ anti-pharma guys as being consulted by a pharmaceutical company. It has a going over to the dark side quality to it. People will be able to say of you that you only have these views because you are being paid – and of course some people will say this.

A.I. sides with industry and with my friends. Putting a current Healy legal report into ChatGPT and asking it what the problems are with it, turns up a 4000 word, 8 page ChatGSK response nearly as long as the core expert opinion section of the original report.

Throughout the report, Dr. Healy’s tone betrays a strong advocacy stance. Phrases like giving the patient “a poison in the hope of bringing good out of its use” to describe an SSRI, or calling the medical literature “ghostwritten… adverts”, are inflammatory. Such language is not typical of a dispassionate expert witness [and] could raise questions about the expert’s impartiality.

An effective expert report should help the judge by illuminating facts.

All the above issues – scientific overstatements, legal missteps, inconsistent reasoning, and intemperate tone – ultimately affect how persuasive and admissible the report is as expert evidence. An expert opinion must be grounded in recognized science and delivered with objectivity and care to assist the trier of fact.

There are many amusing insights here. The bolding is Chat GPTs not mine. I’ve picked two bits out. One to illustrate the emphasis on tone – scientists should be dispassionate, disinterested, dealing with figures not people. Does the bolding suggest ChatGPT’s tone is slipping?

The second is the word fact. And especially the phrase ‘the trier of fact’.

Purity of tone comes with problems when we are asking to participate in trying facts.

Scientia and Science

At the end of last year, Britain’s General Medical Council struck off a doctor for claiming the Covid Vaccines Lacked Effectiveness and Safety and that it was astonishing that so many healthcare folk were supporting vaccinations. The doctor, GMC said, was offering opinions rather than facts and inviting the public to believe his opinions because he was a doctor. It was in the public interest that he be stopped from making claims like these implying they were facts rather than opinions supported only by his status as a doctor.

Before we got science c.1660 we had Scientia – a Latin term for pure knowledge, as is found in logic and some mathematical theorems.

Logic is an operational, algorithmic, procedure that enables us to come the same objective conclusion in a specified situation that everyone else for all time will come to.

In contrast, daily life from time immemorial involved having opinions, which were viewed as a lesser form of knowledge, highly subjective and ephemeral – even though they were critical to survival.

After the rise of science, philosophy continued to seek eternal truths. One path to this was logical positivism. (Someone hopefully will be able to comment on the interface between A.I. and logical positivism).

In contrast to Scientia, how does science, which is constantly subject to revision, get to objectivity or truth? The answer is it borrows from Law, which, some decades before science, decided the route to objectivity was to get a jury of 12 people with disparate opinions, beliefs and backgrounds to attempt to arrive at a consensus on observables in front of them.

This consensus created a fact. Facts are open to revision if new evidence comes along.

There were some stumbles on the way. Walter Raleigh was executed on the basis of what came to be called Hearsay – testimony jurors could not observe being delivered and cross-examined firsthand. Pharmaceutical company assays (studies) are a modern exemplar of Hearsay. The Rules of Evidence in legal cases since Raleigh ban Hearsay.

For nearly 3 centuries, science aimed at getting juries with disparate opinions to attempt to achieve a consensus on demonstrations happening in front of them. Replications, and tweaking of the experimental machinery to see what happened, were encouraged and accepted as a route to revising views as to which facts were established.

The peer reviewed literature was designed to allow others on the far side of the world to repeat the demonstration, making for an enlightened universality.

Medical Science

After 1800, clinical practice grounded in a medical model, became scientific in this sense. Public health initiatives, case conferences and clinical consultations (ideally with both doctor and patient participating) became venues where facts were tried. If the consensus was correct, the patient might have a better chance of surviving. If wrong, the patient might die prematurely. Progress in medicine, especially the dramatic improvements in life expectancy after The Great War, linked to public health and surgical developments, suggested medicine was on the right path.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a set of new pharmaceuticals brought two operational elements into the mix – randomized trials and a set of statistical procedures. These operations claim to offer an objectivity but it is not the objectivity of science.

In the hands of pharmaceutical companies, these operations are spun as science and contrasted with anecdotes (opinions, likely misinformation) but this ‘science’ is better viewed as Scientia with the proper contrast being Facts not anecdotes.

Scientia (RCTs and statistical tests) generate non-existent averages. There may offer an element that allows drugs to be licensed but they tell a doctor nothing about how to treat the person in front of them. They operate in a virtual world rather than the real one.

Few if any of the statistical operations have demonstrated a solid grounding in clinical reality. They may assist us but their use should always depend on an act of consensual judgement to decide whether their use in particular situations helps or hinders.

These operations intruded into clinical care and became a serious, and at present unresolved problem in the early 1990s. In 1991, the Evident capacity of SSRI antidepressants to cause suicide in some people, using traditional clinical methods to establish causality, lost out to some extent at least in clinical settings to the new Scientia.

Can Medical Science be Saved?

Juries and judges remained somewhat immune to the argument that there are no grounds to say that this man murdered his wife, just because no clinical trial has ever or will ever show that on average husbands murder wives, even a trial or epidemiological study restricted to men with a criminal records, legal and financial problems and wives that no-one likes.

Any non-medical and non-expert trier of fact on a jury in a legal setting will ask for the details of the case.

Guided by regulators (bureaucrats), hemmed in by threats of legal actions and losing their jobs, when it comes to trying facts in clinical settings doctors unfortunately are more inclined to practice according to the Scientia and less and less inclined to engage with their patients in trying facts.

ChatGPT doesn’t seem to understand this.

No legal system to date has addressed the fact that a great deal of the evidence presented by experts in cases involving pharmaceuticals is Hearsay and derived from an operational logic that is not designed to help a trier of fact either in a clinical or legal setting.

When it comes to drug-induced injuries, justice requires someone, informed by medical experience, to help a jury see how many doctors shaped by their experience are likely to read certain clinical signs and symptoms. Increasingly, however, this needs to be supplemented with some account of how we got to a position where what might be very Evident to a jury just wasn’t evident to the doctor treating the patient.

See

Our current problems stem from importing medieval operations stamped with a guaranteed-to-offer-objectivity imprimatur. Legal and clinical systems need to return to working with what is Evident in the case in front of them rather than what gets branded as Evidence. A jury of us and our peers is much more likely to be fooled by Evidence, especially Evidence designed to fool us than by what is Evident in front of us.

We also need a chronicling of how we managed to turn the clock back on medical science.

Pharmaceutical companies specialize in commissioning other companies set up to manufacture statements appearing to offer a professional consensus from this or that medical body as to why this or that pharmaceutical sacrament (something that can only do good and cannot harm) should be consumed by the faithful as assiduously as possible.

In contrast, it is very unusual these days to see a bunch of clinicians and researchers come out with a consensus statement on a treatment’s hazards and figure women need informing about these possibilities so that they will be in a better position to engage in a trying of the facts when needed.

This is what led me to pick out the Bauer and colleagues consensus statement as exemplifying what to my mind we need more of – not just courageous researchers but also journals willing to publish statements like this.

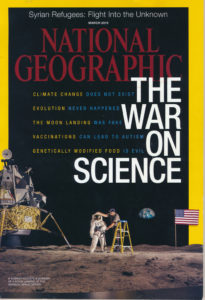

We are up against a semi-Religious War on Science launched by forces whose slogan is Science will win

We need to hold onto our Values. Science is not value-free. It values data and people are the data in medicine. The figures from clinical trials are 2-D abstractions from the data. If it is not possible to interview the people from whom the figures comes, we have no context with which to understand the figures.

There is another value that lies at the heart of medicine and that medicine contributes to modernity. Science fostered the enlightenment and its mission statement Sapere Aude – Dare to Know.

Medicine challenges us to Fidere Aude – Dare to Trust Me.

In recent decades doctors have lost the ability to recognise and work with someone who brings them an insight that is not in their books. While we want some doctors to remain alert to the possibility that some people are trying to game the system, medicine cannot work if most of the people who bring a problem to us are not believed.

As Challenging my Doctor to Disclose says – a key question for those of us going to a doctor these days is likely to be – Why Do you Not Believe Me?

When challenged on key points, the GSK spokesman said, as many in the industry say, that he and the process in place was not in the business of coming to value judgements. Their task was to amass evidence.

ChatGPT doesn’t seem to understand this.

The trier of fact. Totally gives the game away. AI will always betray it’s ignorance. It’s like receiving a scam email from Amazon.

Two examples come to mind on Judgement of Values.

Last year there was an article in the Daily Mail, about the death of Thomas Kingston. It centred largely on large debts of his company. BUT in the article it named David Healy as the expert witness who was of the final opinion that Thomas Kingston, his death, was due to the actions of his doctor, who made a profound mistake, with her prescribing, and Thomas shot himself in the head because of a severe reaction to his antidepressants. The comments section did not make one remark about SSRIs, they all centred on huge stress from money worries.

The horrifying attempted suicide of Dr. David Cartland, whose crime was to believe that Covid jabs were not safe and effective. It also appears that he has been relentlessly bullied by three anonymous doctors. David Cartland was struck off recently by the GMC.

The Value of Judgements, can go from one extreme to another.

A spokesman for GlaxoSmithKline, Alan Chandler, said: “We were surprised at the verdict. This is a tragedy caused by severe depression and not its treatment. There is no reliable scientific evidence linking the use of paroxetine to the events in this case or to violence generally.”

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1173337/

Meanwhile, Romain and Dexter, remain in limbo.

Joining the ‘dark side’ is well worth the effort.

Scientists accused of downplaying dangers of antidepressants

Row breaks out over risk of patients experiencing severe withdrawals

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gift/566d0c394ba870aa

A row has broken out between scientists over whether antidepressants cause dangerous withdrawal effects.

Researchers at Imperial College and King’s College London have been accused of endangering patient safety after publishing a study suggesting that most people do not experience severe withdrawal after coming off the drugs.

New Research Questions Severity of Withdrawal From Antidepressants

Warnings about withdrawal from antidepressants have rippled through society in recent years. A new study claims they are overblown.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/09/health/antidepressants-withdrawal-symptoms.html

“I’ve certainly had patients at my clinic thinking that they shouldn’t go on antidepressants when that was what I would recommend,” he said, adding that patients should be reassured by the new analysis.

“It’s quite clear that you can have some effects when stopping antidepressants,” he said, “but these are a limited number, and they do seem to decline over time.”

Scientists warn antidepressant withdrawal symptoms are being downplayed

https://www.the-independent.com/life-style/health-and-families/antidepressant-withdrawal-symptoms-risks-long-term-study-b2786341.html

Kim Witczak@woodymatters ·17h

Spot-on video by@Fiddaman calling out the recent study downplaying the severity of antidepressant withdrawal.

But let’s ask the bigger question: Why now? What’s the real agenda behind this timing?

Was this study designed to discredit the thousands and thousands of lived experiences of people struggling to come off these drugs?

To protect the image of psychiatry?

To preserve the reputation (and revenue ) of their sacred pills?

Because from where I sit it sure looks less like science… and more like spin.

It left me wondering if this is somehow linked to the recent Benefits challenge in UK Parliament. Get the idea out there that withdrawal, especially protracted withdrawal, is short-lived and there’s your chance to take many people off their PIP and/or Universal Credit benefits.

It’s now up to us to continue to shout out loud and clear that psychotropic drug use/withdrawal as well as covid vaccine damage and Long Covid are the cause of the rise in cases of benefit claimants. In other words – it’s NOT the people that are to blame!

Ive come to the conclusion the courts will do anything to protect the system and corporate world first before they will ever protect any human being. It’s standard practice for them. Just look at the post office scandal as an example.

I was shocked at my courtroom trial at how they control what you can say and what you can’t say to the point you are not able to say what you want to say..

It’s like it’s all a game to them but to you it’s your livelihood at stake. It’s a shocking system that’ feels totally .unjust.

Very few people have any faith left in the system. The whole thing is a farce.

Nothing gets my goat * more than interacting with the UNTHINKING – those who believe themselves to be intellectually superior, but who are, in fact, mesmerised by scientism (my simplistic modern version of your scientia I think), a robotic tone – and the mirage of objectivity. There is no such thing as a thought that is not in some way influenced by a preconception – except, as you say, pure logic – which is arguably an absence of thought.

And yet, as you also say, these same people go home and presumably understand why their small child is looking green around the gills having scoffed too many chocolate buttons and their partner wants to leave them – without having to do an RCT? Or maybe they don’t.

Every so often on X, one of the UNTHINKING quotes the extremely anachronistic hierarchy of evidence to undermine the significance of an individual patient’s iatrogenic experiences. There seems to be a sort of cultural tension or battle between the voice of the person as amplified by social media and the sort of scientism intrinsic to a soulless AI.

Your work as a legal expert in cases of actual iatrogenic harm and/or precautionary risk as in the case of acetaminophen/APAP/ paracetamol is surely cutting edge science. Not just that it has enabled you to access the whole truth and nothing but the truth in terms of research evidence. But is there any more precise scientific endeavour than disentangling the many threads of a complex human life and proving that a drug, taken as prescribed, has caused life changing or life destroying harm?

An attempt was made to teach me the principles of Logical Positivism at university. I vaguely recall being encouraged to join in silly, in fact, ludicrous philosophical exercises in LP argumentation like – ‘how do you know there isn’t an elephant outside the door?’ One of my wagginsh friends retaliated with an essay entitled, “Logical Positivism is a Wasm.’ I felt vindicated reading this just now:

‘Logical Positivism did not fail because it denied human emotion. LP failed because it tried to reduce the concept of meaning to the process of verification, and it became increasingly clear that this was an impossible task.’

https://philosophy.stackexchange.com/questions/65051/did-logical-positivism-fail-because-it-simply-denied-human-emotion

Your reference to it couldn’t be more apt.

* Never used this expression before but always found it tempting. You’re bound to know, but I didn’t – it’s from racing, goats parked in the stall with highly strung thoroughbreds apparently kept them calm. I’m in need of a goat or two. https://goatberries.com/2011/03/the-origins-of-get-your-goat/

Let me introduce a ‘tricky’ point. Is there a particular problem today talking about adverse effects in pregnancy.?

One feature of the Kilker Birth Defects case in 2009 was that it ran up against a campaign – whether marketing or something in the air at the time, that said 80% of pregnant women will have a mental illness at some point in their pregnancy. The implication was that if this was ignored or healthcare folk do anything except do all they could to make them feel happy and comfortable was to treat them like second class citizens.

A moment’s unhappiness or in a second class citizen role could harm a baby so you must treat yourself first.

If this plays a part in acetaminophen being the most common drug taken in pregnancy and antidepressants being the most common drugs taken all through a pregnancy, where does it come from? Is there a way to combat it? Should anyone date think it should be combatted?

There is no suggestion here that women should take nothing in pregnancy.

The issue is a culture of the times one. Several years ago I was astonished to find some women I think highly of – bioethicists – advocating running trials of vaccines and drugs in pregnancy – because pregnant women are ‘entitled’ to the best quality evidence. They are entitled to the best quality evidence but it seems to me to be plain lunacy to think company assays/trials are good quality evidence never mind the best quality evidence. To press ahead and still say trials should be run in pregnancy feels like some kind of tokenism.

Have I got this badly wrong? Am I phobic about women becoming first class citizens. Should I have said pregnant persons becoming first class citizens? Am I imagining a common thread here?

D

Thalidomide conjures up a strong image of birth deformity.

Current pregnancy drug trials are designed to avoid a re-run of this.

Drug safety is determined on the basis of miscarriage and fetal abnormality rates tests in pregnant rats and rabbits.

That something prescribed and taken during pregnancy might cause neurodevelopmental disorders in children that only come to light several years later seems to be of no concern to the regulators.

I wonder how many bioethicists would be comfortable participating in a drug/vaccine trial while pregnant?

I think you underestimate bioethicists. They would push their own prepubertal children onto puberty-blockers at a hint of a whim. The autonomy of the individual takes first place above all other considerations in many bioethical universes. It’s part of the reason the transgender story has gained such traction.

D

Right after reading this, this article popped up in my feed:

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2022/08/mental-emotional-pain-tylenol-acetaminophen-relief/671226/

“Wouldn’t it be nice to have a handy tool to blunt everyday mental pain a bit? Not to become numb to life, just to take the edge off, especially when it is interfering with normal life, the way you can swallow Tylenol when your back hurts. It turns out there are safe and healthy methods to do exactly this, including taking the same sort of painkiller for what ails your body and your mind.”

“If all else fails, or you simply need easier relief to make it through a tough day, you always have acetominophen. I wouldn’t recommend this as your first or only line of self-care, because it doesn’t address the root of your issues, just some symptoms. But in a pinch, it can help.”

In other words — if you don’t like the way you’re feeling, you can just pop a pill to change your mood! What an amazing idea! What could possibly go wrong? Why didn’t anyone think of this before?

I’ve been reading round this topic – becoming increasingly – APOPLECTIC.

The WHO decrees :

‘Vulnerable population – complex population

Until recently, pregnant persons were categorized alongside children, prisoners and individuals with intellectual disabilities as a vulnerable population. Yet unlike these populations there is nothing about pregnancy per se that constrains a person’s ability to provide valid consent or make them particularly susceptible to exploitation. This designation is therefore inaccurate and had a chilling effect on research in pregnancy. Ethical and regulatory guidance no longer uses the term vulnerable to describe pregnant people some instead designate them as a complex population to capture the scientific and ethical complexities that research in pregnancy’.

Ofc there is something about pregnancy that constrains a person’s ability to provide valid consent – they’ve got a vulnerable baby aka child inside them with no voice, choice or critical, decision-making faculties. This has always been the ethical argument against testing drugs on pregnant women (and anyone else with a womb who chooses to identify and self-define in some way other than woman) – and what conceivable reason can there be for over-ruling it now? Apart from the commercial benefit of being able to claim safe to take in pregnancy – on average. A chilling effect on research – what?

I tried reading the draft EMA guideline on including pregnant and breastfeeding ‘individuals’ – women (and other womb owners – so thrilling the UK Supreme Court has given us women permission to self-define biologically – as women) – in clinical trials. And concluded that the authors must be a different species from my instinctive, commonsense, obviously intellectually deficient, short of bioethical theory learning, cavewoman variant. There seem to be no babies or rights of the unborn in their carefully chosen phrases in the ‘Ethical considerations’ (!) section e.g.:

‘Consideration should be given to the use of IRBs or ECs experienced in working with pregnant and breastfeeding participants. For protocols involving pregnant or breastfeeding individuals, this responsibility involves considerations for the participant, for their pregnancy, and the fetus or breastfed infant. Ensuring ethical conduct of the trial therefore requires additional considerations regarding any need for appropriate safeguards related to pregnancy or breastfeeding (including risk mitigation measures implemented in the protocol and stopping criteria), as well as additional considerations regarding informed consent (Sections 4.4 and 5.5).

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/new-guideline-inclusion-pregnant-breastfeeding-individuals-clinical-trials

As far as I understand it, thalidomide was not tested on pregnant animals – as it and any other drug that pregnant women (or other womb owners) might take, should be – properly But:

‘Trials with rabbits demonstrated the fetal toxicity of the drug in 1962, months after the withdrawal of thalidomide from the German market. These results were confirmed through additional trials with several other species of small mammals and eight species of monkeys over the following 10 years.’

https://fbresearch.org/thalimodide-tragedy-animal-testing

Just as it was perfectly clear from retrospective studies amongst women with epilepsy and animal studies done on valproate in the 1970s that the risks of teratogenicity were there for all to see – but intellectualised into a familiar ‘multifactorial’ low risk argument:

‘The malformations probably have a multifactorial ætiology, and, while anticonvulsant drugs may have a teratogenic action mediated by interference with folic-acid metabolism, such teratogenic activity is likely to be influenced by hereditary and environmental factors. For the individual mother with epilepsy the risk of having an abnormal baby is low.’

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(72)92209-X/fulltext

So, here we are half a century later in the UK – and presumably other countries like France where both Sanofi and the regulator are being sued for failure to warn re teratogenicity – insisting that patients with epilepsy are not just fully informed, but the system is actively aiming to control their reproductive behaviour with a Pregnancy Prevention Programme (PPP).

There is further ethical complexity in that some women with epilepsy, forced to use valproate to control it and thus not only enable them to live but avoid death – are understandably feeling ‘eugenicised’. They, like many of us women, not all, are instinctively driven to reproduce, and some are choosing to become pregnant in spite of the known teratogenic risks – and, reportedly and happily, have given birth to healthy babies.

A report into maternal deaths MBRRACE-UK’s Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care 2023 has raised further issues – ‘17 women died from causes related to epilepsy, and 14 of these deaths were due to Sudden Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP). The researchers highlight that the period that saw the rise in deaths due to SUDEP was also a time of significant changes to the prescribing practice for the anti-seizure drug sodium valproate. None of the women who died in this period were taking sodium valproate’

But, equally. it wasn’t clear whether they were taking their anti-seizure medication ‘properly’ either.

The bottom line, from my intellectual cavewoman perspective, as Ann Bauer et al wrote in the Consensus statement on APAP, is that is precautionary principle is the only ethical way to go. When animal studies and drug affects that accumulate in registries indicate that there are risks to the unborn child, neurodevelopmental, premature birth etc, potential breeders, women and other womb holders, need to know.

Clinicians and manufacturers, who seem to be the most resistant to assimilating new information about risk – should (prescriptive) be required to get their heads around the notion of the precautionary principle too – and start telling their patients the truth.

Fulminating about experimenting with drugs on unborn babies and littering DH with cross typos – I forgot to say…

Thinking about your ‘culture of the times’ question – one dimension worth considering is national maternity cultures. An obvious country differentiator is the degree to which they embrace natural childbirth beliefs and practices or more interventionist ones. I’d guess the former would be more receptive to communications about chemical risks in pregnancy, even risks from familiar, friendly, cheap household drugs like paracetamol.

The Netherlands is by far the global leader in midwife-led, natural childbirth – with half the C-section rate of countries like the UK and US.

The UK was similar – in the 90’s waterbirths took off, NCT classes taught breathing techniques, back massage, how to avoid an episiotomy etc. But all this changed in the early 2000s with an epidemic of tragic maternity scandals. No mother can feel wholly reassured about the safety of giving birth in the UK – not even to this day:

‘In the commission’s latest report, published in September, not a single one of the 131 units inspected received the top rating, Outstanding, for providing safe care. About a third (35%) were rated as Good for safety, around half (47%) were rated as Requires Improvement while Almost a fifth (18%) were deemed Inadequate, the lowest grading.’https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/clyn8n3nyrlo

Of course the problems are dysfunctionality throughout the system – lack of continuity of care, strife between midwives and obstetricians, a failure to listen to patients , particularly those from BAME communities etc. But there’s also been a backlash against what’s seen as a midwifery ideology – ‘natural’, vaginal birth at all costs – associated with dangerous delays in interventions etc.

Finally getting to the point – what this means is that UK maternity is obviously under intense pressure – and, in stark contrast to the wholesome, cheery Netherlands, could be described as neurotic. Its focus is minimising risk– and ‘mental health’ is emotively risky territory.

The guidance on SSRI risks to the foetus – is lightyears away from Bauer et al’s wise and decent precautionary principle, e.g.

‘Some studies show an association between SSRI use in pregnancy and an increased risk of miscarriage (odds ratio about 1.5), low birth weight, and preterm delivery, but data are conflicting, and it is possible that maternal depression may be a confounding factor as these outcomes have all been associated with this condition.’

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/depression-antenatal-postnatal/management/planning-a-pregnancy-on-an-antidepressant/