Editorial Note: This is the fourth in the Lasagna series of posts – Not So Bad Pharma, April Fool in Harlow and Tragedy. It will be followed by The Empire of Humbug: Not so Bad Pharma, Brand Fascism & Witty A: Report to President.

The first RCT

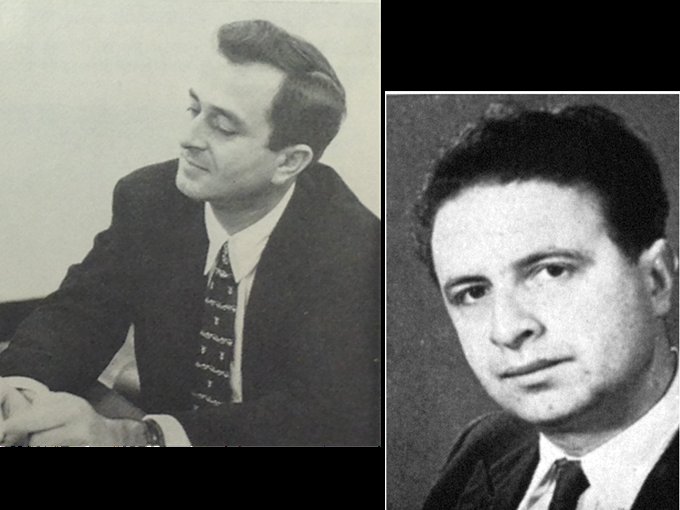

In 1956, two of the creators of the modern RCT, Lou Lasagna and Michael Shepherd, met. The randomization in randomized placebo controlled trials came from Bradford Hill in Britain and placebo controls from Beecher, Gold and Lasagna in the US. In 1956, Michael Shepherd, Bradford-Hill’s representative in all things psychiatric, came on sabbatical to stay with Lasagna at Hopkins’. [Lasagna is on the left].

In 1947 Bradford-Hill ran the first randomized trial. In 1955, Shepherd added in Lasagna and Beecher’s placebo to the original randomized design and published in the Lancet the first ever RCT of the type used today in drug trials submitted to FDA for regulatory approval. His trial compared reserpine to placebo in a group of outpatients with mixed anxiety and depression – similar patients to those later given Prozac and other SSRIs. Reserpine was better than Prozac and other SSRIs later were, and indeed did better than imipramine did a few years later in a trial run by Lasagna. There was no sign in Shepherd’s trial of the suicide hazard for which reserpine is now best remembered.

The two articles that immediately preceded Shepherd’s study in this issue of the Lancet described hypertensive patients being treated with reserpine who became suicidal. When later asked why his trial had almost no impact, Shepherd’s off-the-cuff response was that doctors were not used to seeing results being presented in this way. But there was in fact no commercial incentive for any company to use his results to relegate the accounts of suicide on reserpine to the status of anecdotes.

Evaluating drugs

Just as Shepherd’s paper was published in 1955, chlorpromazine was taking the American market by storm and looked set to change psychiatry as much as penicillin had changed medicine. This earthquake in therapeutics led to a landmark Evaluation in Psychopharmacology meeting convened by Jonathan Cole and Ralph Gerard in Washington in September 1956, at which Lasagna was a key note presenter. Shepherd attended.

Critically just 6 years before it became a legal requirement to use controlled trials and only controlled trials to evaluate drugs, there was no controlled trial section to these proceedings. Instead, there were notes of caution about clinical trial methods from the grandees in the field – positions that years later Lasagna endorsed.

Fritz Freyhan criticized a naïve faith in technical objectivism:

“the time, we hope, has not come when the clinician abdicates and the rating-scale marker takes over as a judge”. “While one can easily spot the potential and actual shortcomings of nonexperimental studies, it appears to be tremendously difficult for multidisciplinary groups to acknowledge limitations and sterility in rigid experimental design”.

Nate Kline said a rating scale approach to clinical evaluation risked creating a rabbit-out-of-the-hat illusion. Pulling a rabbit out of the hat depends critically on getting the rabbit in there first – which was what rating scales did for drugs.

Ed Evarts noted that if chlorpromazine and controlled trials had been invented a few years earlier, chlorpromazine would have been shown to “work” for dementia paralytica (neurosyphilis) and its use would likely have inhibited recognition of the fact that penicillin was a cure.

Shepherd and Lasagna’s faith in controlled trials was a minority taste within psychopharmacology.

The two men born in 1923 had contrasting styles. Shepherd was aloof, drew lines in the sand and made enemies. Lasagna was sociable, worked to find areas of agreement and retained the affection of many who took opposite points of view. Shepherd’s insistence that controlled trials were absolute embroiled him in a set of bitter disputes about lithium that derailed his career. Lasagna viewed controlled trials as a pragmatic option, but his pragmatic insertion of controlled trials into the 1962 amendments led to a bureaucratic absolutism that also derailed his career (see Tragedy).

Although not a psychiatrist, Lasagna ended up with a wider following within mental health than Shepherd for two reasons – his work on placebos and on rating scales.

The humble humbug

While Lasagna was not the creator of the placebo, Gold, Beecher and others did earlier work (see Tragedy), his 1954 paper with Beecher ended up in Medicine’s top 30 cited articles ever and put placebos into RCTs. The placebo for most people, lay or medical, at this time was a form of hypnosis – a bridge between psychodynamics and pharmacology.

The hypnosis myth was fostered by a 1954 editorial on the placebo in the Lancet entitled The Humble Humbug. The phrase stuck. At a time when magazines were emblazoned with titles about miracle drugs, a Readers’ Digest piece in Sept 1956, coinciding with the Washington meeting, ran a piece on “perhaps the most remarkable of the miracle drugs” under the heading of “Medicine’s Humble Humbug: The powerful role in sickness of mental attitude”. By the time the Readers’ Digest piece came out, however, both Lasagna and Shepherd were reaching for a more unsettling understanding of what placebos might mean (see forthcoming Empire of Humbug: Not so Bad Pharma).

The second contribution came in demonstrating that rating scales could be used to test analgesics and hypnotics. This persuaded the field it was possible to objectively study internal mental states and in so doing Lasagna laid the basis for the insertion of controlled trials into psychiatry.

But there’s a rub. When we think about effectiveness, what do we mean? Without rating scales we might have to show treatments saved lives or got people back to work.

Lasagna was one of the first to appreciate the ambiguities in what seems like a simple question. It could mean – how good is this drug? Alternately it could mean – have the benefits of this drug been proven to be greater than the harms?

In 1962, although Lasagna appreciated these ambiguities more than anyone else, with the thalidomide crisis the pragmatic need was to find some basis for inserting an effectiveness criterion into regulation. The Democrats whom he was advising wanted one. The Republicans and business didn’t. The struggle came down to a battle over words – whether the preponderance of the evidence should support the application or whether the existence of a substantial amount of supporting evidence would suffice.

Lasagna came up with a winning formula – the application should be supported by evidence from adequate and well-controlled trials conducted by suitably qualified experts. This became two adequate and well-controlled RCTs, because ordinarily in science if a finding is replicated we can rely on it.

Based on science

The 1962 amendments to the Food and Drugs Act and in particular the effectiveness criteria form the centerpiece of FDA’s proudest boast, repeated widely, that these amendments were the first example of regulation based on science.

The claim gives rise to a myth – that “scientists” from FDA are supposedly keeping the public safe. The myth is found everywhere from academic commentators on the FDA, as in Harvard’s Daniel Carpenter’s Reputation and Power, to views from the popular end of the spectrum, as in Philip Hilt’s Protecting America’s Health. There is no questioning of the mantra.

Not since the Wizard fooled the citizens of Oz into thinking that he was keeping them safe from the Witches of the West and the East and all dangers in between have we been so misled.

Controlled trials are based on a null hypothesis. Their early use was to debunk claims that treatments were effective. The trials we celebrate most, such as the Women’s Health Initiative Study of Hormone Replacement Therapy, continue to be ones which show how powerful this debunking can be. They are not a natural means to test for effectiveness.

If the controlled trial formula had been restricted to rejecting applications for treatments that didn’t work, companies who thought they had a good treatment but whose compounds failed in clinical trials might have had to go back and pick out a sub-group of patients the treatment clearly did benefit, for instance.

Testing for a negative is an unnatural frame of mind. The gestalt flips into viewing a disconfirmation of a null hypothesis as evidence that something positive has been demonstrated. When this happens, RCTs become a potentially invalid and certainly ambiguous metric.

The idea that what they were doing was based on science appears to have engendered a bureaucratic hubris. Regulators certainly don’t act like they have let a drug on the market because they cannot say it’s not effective.

But what if there have been five studies – two positive and three negative? In both cases the science has been replicated. In this instance the drug is let on the market, as the regulatory criterion has been met. When this happens the regulator demonstrates he is solving a regulatory problem rather than engaging in science and that regulation is about the mindless application of a bureaucratic rule.

As regulating takes place against a background bristling with the legal resources a pharmaceutical company can bring to bear on decisions that are not congenial to their interests, while it was briefly different leading up to the Panalba case (see Tragedy), FDA staff now learn quickly that regulation is unquestionably about the mindless application of a bureaucratic rule.

The rule says that it takes two positive studies to approve a drug. In law, if there were only two positive studies out of 100, the regulator would approve the drug. They have in fact approved applications where only 1 in 5 studies were positive. A variety of justifications are brought to bear on the issue, never found in science, such as the notion of failed trials. The bottom line is the studies in which the null hypothesis is upheld and the claims for drug are not upheld, do not count.

One consequence of this is that there are now tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of trials in pharmacotherapeutics, while there may still be less than one thousand trials in surgery and as few in preventive medicine. But where the practice of surgery has made dramatic strides, in many areas of pharmacotherapeutics the field has gone backwards.

Catch 62

Aside from the fundamental confusion between the scientific process and regulation, there are a series of profound misunderstandings that have made the 1962 amendments close to a disaster.

The word effective is a key problem. The regulations call for demonstrations of effectiveness while a great deal of the talk in 1962 featured the word efficacious. Treatments meanwhile also have effects, both beneficial and adverse.

Since 1962, effectiveness has come to be defined as evidence that treatments work in the real world. Virtually no drugs brought on the market demonstrate effectiveness in this sense. Almost by definition effectiveness cannot have been shown to be present whenever a study uses a surrogate marker or a rating scale score as its outcome measure.

Efficacy is used when a treatment does something useful in controlled trials but benefits are not necessarily realized in the real world. Almost all industry trials have to fall under this heading, if only because they come with so many real world exclusions and involve samples of convenience rather real patients.

An effect is an action on a structure or function of the body that may be beneficial and is something that may or may not take a controlled trial to demonstrate.

The 1962 Act uses the word effectiveness. There are other definitions of these words but whatever definitions are used there is no way to semantically solve the issues we are tackling here. The 1962 amendments are fatally flawed.

A subsequent regulation (CF 310.3 (4)) is more ambiguous:

The newness of use of such drug in diagnosing, curing, mitigating, treating, or preventing a disease, or to affect a structure or function of the body, even though such drug is not a new drug when used in another disease or to affect another structure or function of the body.

Randomized placebo controlled trials have not shown any drug within the mental health domain is effective. If a treatment were effective virtually every RCT undertaken would show a positive result.

Some psychiatric drugs are extraordinarily effective, for instance benzodiazepines for catatonia or SSRIs for premature ejaculation. These treatments are so effective that controlled trials are an irrelevance. Every trial conducted would show a positive result. The point here, developed below, is not that it is impossible for a treatment to achieve effectiveness but rather that controlled trials have little useful to contribute to the issue of effectiveness.

The public and legislators have been baited with effectiveness and sometimes efficacy but sold something else that doesn’t fit neatly under effectiveness, efficacy or effect. Some of these issues are now the subject of consumer fraud actions.

The Kefauver hearings centered on analgesics, hypoglycemics, tranquilizers and steroids. With each of these drugs there is an obvious effect but is there effectiveness? Hormone replacement therapy has an obvious effect but when a proper study was undertaken it turned out to be ineffective for the benefits claimed for it. For most doctors in the 1960s, Upjohn’s oral hypoglycemic, tolbutamide, clearly worked – it lowered blood sugars. But when a large controlled trial was undertaken in the late 1960s tolbutamide led to more deaths than other forms of treatment – was it effective?

The tolbutamide and HRT trials took 5 or more years to run. No one would ever suggest companies should go through trials like this to get on the market – certainly not Lasagna. This is what trials are for though. They are not for getting drugs on the market. The difference between WHI and NIH trials and company trials not about one set of trials being independent and the other not – it’s about the purpose of the trial.

If a short-term hypoglycemic or tranquilizing effect seems on the surface beneficial, it might be possible to talk of efficacy but this falls short of effectiveness, not because of something mysterious that happens when we move from clinical trials to the real world, as the definitions above suggest, but because while useful in both trials and the real world these effects are not effective in the sense of curative.

Analgesia and tranquilization are therapeutic principle rather than Magic Bullets.

Therapeutic principle or magic bullet?

Part of the problem is that antibiotics have skewed our notions of what drugs should do. They have created a Magic Bullet template. It is all but assumed that if a treatment is approved it maps onto this template when in fact most treatments in medicine are helpful rather than curative – they are therapeutic principles rather than magic bullets. Analgesia, tranquilization, temperature reduction, or all sorts of other things can be helpful within a therapeutic relationship.

The idea of a Magic Bullet suggests a treatment that works regardless of setting or circumstance. Therapeutic principles in contrast have always been recognized to be dependent on constitutional or temperamental factors and on setting. Agreeing that a treatment “works” or “is effective” (Magic Bullets: MBs) rather than this treatment has an effect that may be beneficial for you (Therapeutic Principle: TPs) risks condemning many to the wrong treatment for them.

Condemning is too mild a word for the forcible medication of many mental health patients with what were once called tranquilizers (TP) but are now called antipsychotics (MBs).

One consequence of Lasagna’s 1962 wording has been to move us from a world of Evident Based Medicine, which he agreed with, to Evidence Based Medicine, which he didn’t agree with. “Evidence of effectiveness” is now used to persuade or all but force patients to take and doctors to give treatments even when they are evidently not doing you good (see False Friends).

If trials indicate treatments are effective, it’s in the interest of the State (as well as pharmaceutical companies) to “persuade” or force as many of the citizenry to take treatment as possible, as clearing up diseases should make the population more efficient. To this end, a certain amount of casualties en route can be accepted as collateral damage. In the case of the antidepressants and suicide, regulators again and again made clear that they would not warn of this hazard, in case people might be deterred from seeking treatment, or doctors deterred from putting them on treatment.

Coming back to Lasagna’s question – what does effectiveness mean? Even when controlled trials show a net loss of life on a treatment, regulators now almost always state that the risk benefit ratio remains favorable. This view can only be sustained on the basis that they believe if the treatment is effective, as for instance in the case of the antidepressants, even if there is a net loss of life from suicide in short term trials, that somehow in the longer run an effective treatment will lead to lives saved.

This is not an evidence based position. It can only begin to possibly make sense on the basis of some belief about an effectiveness that conveniently for regulators is rarely put to the test – the WHI HRT and NIH tolbutamide trials were monumentally inconvenient for regulators but even they didn’t lead to the drugs being pulled. That’s a medical issue not a regulatory issue.

Truly effective treatments should be self-funding or even lead to a fall in healthcare costs. If lives are saved and people are put back to work, or become more efficient at work, then national economies will perform better and wealth will increase. But not only are healthcare costs increasing exponentially, morbidity and mortality from treatment is increasing so that treatment induced death is heading toward being, may even be, the normative way of dying.

None of this should be happening if our treatments are effective. RCTs, as used by companies, may be efficacious to get drugs on the market but for the most part they aren’t effective in leading to better health.

Conversations in the speakeasy

The irrationality of what has happened can be brought out by comparing antidepressants with alcohol. In the case of imipramine, a much more potent antidepressant than Prozac, Lasagna who ran the first RCT on imipramine recognized that it was difficult to even prove efficacy in an RCT.

In the case of the later SSRIs, there is distinct psychotropic “effect” – they emotionally numb. SSRIs “work” in the sense that alcohol “works”. Using the same testing approach that brought SSRIs to market that supposedly demonstrates their effectiveness we could bring alcohol to market as an antidepressant or anxiolytic if it could be patented so that it was worth our while. All it takes is a result in two of ten short 6-week trials, in which it would have almost certainly produce a “benefit” on the right rating scales and with fewer serious side effects than SSRIs – there would not be a doubling of suicidal acts, with up to 5% of patients having suicidal ideation as there is with SSRIs (see Shadow Dance).

Because everyone knows what alcohol does, they can see that such a demonstration for alcohol is not a demonstration of effectiveness, but they seem unable to see that this is also the case for SSRIs, for every other psychotropic drug, and for a majority of drugs in medicine.

If we were to try and bring alcohol on the market, we would do so on the basis of its effect on a structure or function of the body rather than for supposed effectiveness. What would the world have looked like if the same had been done for the SSRIs?

At the end of his career, Lasagna mused “The days when a drug company [developing a drug] would go to skilled and sophisticated psychiatrists [like Fritz Freyhan] and give them a supply of a new drug and ask them to try it on some different patients seem gone forever. Is this a cause for celebration or depression?”

Before an effectiveness criterion was brought in, under the 1938 Act, several classes of antibiotics, diuretics, antihistamines, hypoglycemics, anticonvulsants, steroids, antihypertensives, major tranquilizers (antipsychotics), minor tranquilizers, analgesics, antidepressants, stimulants, oral contraceptives, the first chemotherapies for cancer and a range of other highly effective or efficacious treatments were brought to the market, all without the help of controlled trials.

Since 1962, it is doubtful if as many effective medications have been brought on the market. It is likely that more relatively ineffective but highly dangerous drugs have been marketed since 62 than before 62. This is an almost completely predictable consequence of what we have done.

(See Empire of Humbug: Not so Bad Pharma. “Andrew Witty” will also offer a view on what the right wording of Drug regulations should be in Witty A: Report to President).

Thanks for that very interesting interpretation of recent medical history.

Have you done any research on operational definitions in psychiatry? They seemed to be part and parcel of the whole push to make psychiatry more scientific in the 1960s. As a trainee psychiatrist in Edinburgh one of my teachers wars Bob Kendell. One anecdote from him I remember related to a conference on psychiatry which had been dominated by disagreements on the major diagnoses. It seemed that every Department of Psychiatry had its own definition. Bob Kendell described how there was a visiting American philosopher who had stood up and said you will make no progress until you define your terms. From that developed the Maudsley’s romance with operational definitions which became a core part of pharmacotherapy investigation. Kendell went on to do the research that supported the unitary hypothesis of depression rather than the bimodal one based which had been based on depressive psychosis and depressive neurosis (or their pseudonyms). As I had been exposed to structuralist ideas through having a flatmate who had become a follower of Levi-Strauss I had several arguments with Bob Kendell pointing out that the results he gave flowed from the assumptions he had made. He riposted that I was a Platonist. I knew a lot more about structuralism then than now and I cannot fully recall the details. To my mind that positivist error of dividing the world by words and concepts where in truth there is no division has hampered psychiatry for the last 50 years. Anyway enough of my ramblings. You are a scholar and I wonder if this is an area that you have studied.

When you write: “The rule says that it takes two positive studies to approve a drug. In law, if there were only two positive studies out of 100, the regulator would approve the drug” I assume you are referring to the FDA and therefore US law, yes? Is this the same in the UK, presumably with the EMA and/or MHRA?

De Facto its the same in the UK. Not certain what the wording is – would be worth an enquiry. The UK tends to approve faster than the US – so less stringent rather than more so.

I could not let the week pass without mentioning a certain lady of colour and it seems relevant here.

This is all so interesting, my favourite to date, and as a mere bit of collateral damage hanging off the edge of ssris, can I just say that Maggie T. is now considered divisive.

I have not heard the word divisive as many times as I have this week and it is relevant here.

Evidence and evident are divisive. not meaning the same thing at all. Effective and effect are divisive, not meaning the same thing at all.

Divisive means two halfs, split in two, halved, etc. but the sum of the two parts equals whole is not happening.

The War on Words and their acute meaning is a very important part of the ‘science’ behind the rct and the ssri, and where the Humbug comes in, is in the bit of paper in the ‘box’ which all doctors should stick in their bin before giving the packet to the patient……instead, for all it matters, the words to the patient could be ‘pot luck, your call, you’re on your own, I didn’t make the bloody pill’.

I appreciate the moderator usually prefers the scholastic comments, I just like to offer the subjective, simplistic, human interest angle.

Also, a sense of humour is pretty vital, at this moment in time, otherwise, what is left.

As it was said: Witty A. Report to the President.

Wish we had Spitting Image back….Maggie T. was a hoot, Witty A. would be ….not one ‘icon’ was missed out on Spitting Image….

I am not being ‘divisive’, I am just saying Witty A. and President of the US in one breathe is a trick (y) bit of information.

“Controlled trials are based on a null hypothesis.”

I’m looking at this phrase trying to find a comment but I decided that it is not necessary.

They create the hypothesis later.

It that becomes theory following the peer-reviewed methodology,

This is what they name “science”.

Hmm… Ok…

Errata:

“It becomes…” (without “that”)

I have checked the statistical analyses reported by Davies and Shepherd and I cannot confirm a statistically significant effect of reserpine on the primary outcome measure (their global rating presented in Table 1). It’s possible that Shepherd just miscalculated… this done was before desktop calculators and desktop computers with statistical packages came along. I invite anybody else to check it for themselves. It is surely a stretch to say reserpine was equal to later antidepressant agents.

As for the study of imipramine reported by Lasagna in 1961, it is not really appropriate to use as a benchmark for evaluating the putative antidepressant effect of reserpine. Though one has to admire the pioneering effort, reading that report by Lasagna makes clear that it was a messy piece of work, clearly underpowered, plagued by diagnostic chaos, excessive dosing with resultant toxicity of imipramine, multiple dropouts, and an overly complex design (randomized crossover sequence of 4 weeks on placebo and 4 weeks on imipramine). As the authors themselves acknowledged in presenting the Results, “this part of the report is essentially one on the methodology of antidepressive drug studies rather than a definitive assessment of imipramine.”

Barney – this is wonderfully helpful. Definitely worth going back over all these old reports to do just this. But I still think reserpine looks as good as if not better than Prozac and Zoloft. In the case of Zoloft for instance of the first 5 trials done only 1 struggled to be positive so that even FDA reviewers said the data was embarassing. Take a mean of the Zoloft data and reserpine looks better than that.

In the case of Prozac of the studies that got it on the market, one that regulators critically dependence on used a facility used by Louis Fabre in Texas. FDA almost certainly knew then what it knew later which led Fabre to be debarred from doing clinical trials. The data even so are more than embarassing but it is likely that without these data the drug would not have been licensed. The company were pleading to use the separate centers of a multicenter trial as separate trials in order to claim that marginally better results from a few of these centers constituted evidence of several positive trials.

A small interruption to your interesting dialogue.

If I am ‘vaguely suicidal’ in 1988 from starting Imipramine with all the withdrawal there is in the book and an up to date psychologist takes me off it as he said himself,’Imipramine can sometimes bring on acute anxiety and emotionally labile symptoms and it will be ceased’.

I am ill for months afterwards, not having a clue what is going on. In 1988.

Then, in 1999, I am given Seroxat. The man does not check on previous medical history, re Imipramine. He tells the surgery to switch me to Fluoxetine, this is ignored, and six weeks later I am more than vaguely suicidal.

The man said I had no medical history of note, I was not suicidal, I was not psychotic, I was of above average intelligence……

I thought I almost had this man and my surgery over a barrel.

Lax, lazy, inadequate, irresponsible; along with a fabrication re Fluoxetine.

The fact that Imipramine caused me suicidal ideation in 1988, led my Glasgow lawyer to throw out my case re my gp lying about Fluoxetine because following on with Seroxat and suicidal ideation and acts, my experience with Imipramine then proved that I was ‘suicidal’.

I am thankful that Imipramine and Seroxat now come out in the same breath.

Call it bad luck, call it what you will, Imipramine and Seroxat almost did for me….

I left the hospital of this man, who could not even be bothered to check on my medication and four days later….they got me again.

This is the human interest story, once again…….

The truly scary part for me is, if Prozac causes suicide, as well as Seroxat, then my case against the prescriber and surgery are dead in the water……what is the point of switching to Fluoxetine is my main query at the moment…….NICE say switch, MHRA say switch, DH says switch…but…then what might happen….

And….if I do send in a complaint to the MHC, then whom would they refer to about Imipramine, Seroxat and Fluoxetine…to whom would they refer to for advice.

Because if they go to NICE, MHRA, then the circle starts all over again and this becomes a total non-starter.

Nowhere has never been so nowhere.

Carry on with your interesting dialogue, Mr. Carroll and Prof.; just wanted to interrupt it for a second.

A comment on this by Dr. Mickey Nardo from his 1 Boring Old Man blog:

“And now for the problem that haunts us to the present. The six-week clinical trial of Reserpine showed that it was useful in a number of psychiatric dimensions, proven by a statistically significant double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial – the first in history. And that’s correct … Unfortunately, in the long term, it can cause depressions indistinguishable from naturally occurring psychotic depressions – big ones. As we well know, generalizing from the brief clinical trials now used for approving drugs misses a lot of what can happen with prolonged use.”

Was this view of reserpine – that it could be antidepressant in the short run but cause depression in the long run – pretty well accepted in the 1950’s when it was in wide use? Did anyone claim to know what led to this? If so it could be very damned relevant to what is going on today with SSRI’s, SNRI’s etc. I have read articles by G. Fava, R. El-Mallakh and others raising this possibility and saying research is urgently needed – but they seem to be roundly ignored. (Who the hell is going to sponsor that kind of research?)

David, would you possibly be able to offer any hope to someone who has had their brain ruined by psychiatric meds? It’s a long story but I used to have mild to modetate depression before starting meds and now I feel ruined after getting into the psychiatric med system. I live in the U.S. and have been trying to find any doctor anywhere that might can help what these meds did to me. I may be able to travel if I needed to.

I appreciate the incredibly ethical approach you take to the world of psychiatry. It’s refreshing to read your articles and makes it seem their might just be hope left in this wworld for people who need help.

Michael

Its not meant to be incredibly ethical. Much more a concern that doctors are going to go out of business if they don’t realise that a substantial part of their future lies in managing the kinds of problems you have rather than just acting as a conduit to get people on meds. The future lies with informed patients working together and with doctors who can manage teamwork rather than with old style medical experts whose word is law.

Ah don’t let him fool you Michael, it is ethical as all get-out. It has a good sound doesn’t it? Kind of gives you hope, and it’s a lot more interesting than all the prattle about finding the sixth or tenth or 14th drug to batter you with until you are “symptom-free.” But the larger point David makes is very true. We need doctors who can approach their patients as a human being among human beings, and we need to create some teamwork. Otherwise doctors just may go out of business. Of course a lot of them would be just as happy being stockbrokers … but others would not, and those are the ones we are counting on to break ranks.

Even though this is not a mutual-aid board per se, I have to pipe up as someone who has found myself in a similar position but maybe a few years further down the road. So far, no one has an Antidote for the damage that’s been done, and there’s not even any certain diagnosis. No one can put you in an MRI machine, study the films and say “Sorry pal — your soul is gone,” or “Look, there’s hope, 65% of it is still functional.” So a great deal depends on what we choose to believe. Until proven otherwise, I gotta believe they could not engineer a chemical to “save” me so they could not destroy me either. Hope you stick around! We will need a big and diverse team to figure this out.

Much more a concern that doctors are going to go out of business if they don’t realise that a substantial part of their future lies in managing the kinds of problems you have rather than just acting as a conduit to get people on meds.”

But it doesn’t seem like there’s a way to manage many of the problems that meds can cause. Sure a doctor could prescribe Wellbutrin or some other stimulant for “post SSRI sexual dysfunction” but otherwise things like anhedonia being induced by a med like Mirapex serms untreatable in the traditional way we increase pleasure chemicals in someones brain. I’ve been in contact with someone on a forum who has this same problem I have from Mirapex. He’s referring to it as DAWS (Dopamine Agonist Withdrawal Syndrome.) I call it hell on earth.

Too many problem meds cause seem untreatable, even if you get a psychiatris who believes you about it.

Michael

Quite coincidentally, there has been a Rxisk story about DAWS just this week – see http://wp.rxisk.org/sos-dopamine-agonist-withdrawal-syndrome/

I agree there are some terrible problems out there, in particular withdrawal problems. I think few people have any idea of just how bad DAWS and SSRI withdrawal can be. These will be difficult to solve but are much more likely to be solved by the people affected and doctors and pharmacists working in a team to solve them.

Can you submit a Rxisk report and get anyone you know who has DAWS to do so also? Would be good to build a HeatMap of where the problems are and a HeatMap of helpful doctors perhaps