I am among those who can be blamed for the disastrous MHRA supported drug label and messaging for antidepressants, along with Guideline recommendations that tell doctors and patients that it can take 6 weeks for antidepressant induced recovery to take place.

This idea has been interpreted by MHRA and lots of psychiatrists and family doctors, who have no background in pharmacology, to mean that people who are becoming badly agitated or actively suicidal in the days after starting an antidepressant should continue on their treatment regardless – because it can take 6 weeks to recover.

At a time like this, when they are feeling worse and their life is obviously at risk from this terrible disease, they more than ever need an effective treatment.

Here’s how this lethally crazy idea took hold.

SSRIs

Back in 1970 when SSRIs were just a glimmer in Arvid Carlsson’s eye, the focus was entirely on catecholamines – Restoring the Magic to Healthcare. Noradrenaline was low in depression and tricyclic antidepressants supposedly restored it to normal. Julius Axelrod got a Nobel Prize for this work. But there was one big problem. Tricyclics rapidly increase noradrenaline levels, but recovery didn’t immediately take place.

Unlike the muscle relaxation from benzodiazepines, the increased energy on stimulants, or the reduction in tension on antipsychotics, which are clear effects that start within minutes or hours of taking a first pill and remain the obvious therapeutic effect throughout treatment – if that is they are present to start with, there was no immediate onset obviously good thing that tricyclics did. Recovery took about 2 weeks or so to appear.

It was easy to think that rather than having a useful effect, tricyclic antidepressants must be correcting a defect. Everyone at this point still agreed the defect was in the noradrenaline system.

The goal was to make pure noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors in the expectation that these would be more effective and free from the nasty side effects caused by tricyclic actions on serotonergic, histamine and cholinergic systems.

Fridolin Sulser claimed the key lay in changing noradrenaline receptors. Chunks of receptor protein felt like they might take a little longer to change than simple neurotransmitter levels, perhaps even two weeks. Everyone jumped on the Sulser bandwagon.

Meanwhile, Arvid Carlsson came up with the idea of an SSRI. He based this on an almost immediate onset useful effect that some, but not all tricyclics, had. Listening to doctors and patients, Carlsson heard that clomipramine, imipramine and amitriptyline produce an early onset anxiolytic or serenic effect that made them useful for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and other anxiety states in a way that desipramine and nortriptyline weren’t.

Desipramine and nortriptyline are also tricyclic antidepressants. They inhibit noradrenaline reuptake but not serotonin. They are ‘purer’ versions of imipramine and amitriptyline, which inhibit both serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake. They don’t do this something that imipramine for instance does – and it was becoming clear they are in some way weaker than clomipramine, imipramine and amitriptyline.

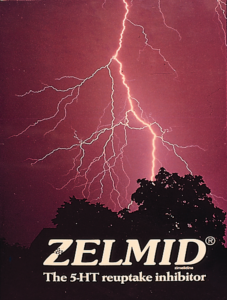

Rather than follow the noradrenaline inhibitor crowd, Carlsson set about making a pure serotonin reuptake inhibitor. He created zimelidine, Zelmid, and then alaproclate, both of which got withdrawn because of problems. But not before clinical trials and early practice showed that Zelmid worked. Carlsson inspired Rhone Poulenc’s indalpine, which worked but was removed because of liver problems. Under his influence, Lundbeck converted talopram, a noradrenaline inhibitor, into citalopram and later escitalopram. Finally, before Prozac, there was fluvoxamine – Luvox – later linked to the Columbine massacre. LTEP

Prozac was about the sixth SSRI, made after Lilly figured noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, like nisoxetine and atomoxetine were not the way forward. Desipramine and nortriptyline were purer but also weaker than their parents, imipramine and amitriptyline, and not especially anxiolytic.

Zelmid, Prozac and all the SSRIs were also pretty weak antidepressants, but this didn’t worry companies. They were serenic – anxiolytic – a bigger market than antidepressants.

SSRIs were/are immediately serenic even in much lower doses than the standard Prozac, Paxil and Zoloft doses. However, selling doctors the idea that, unlike benzos, these anxiolytics would not cause dependence was a problem. This problem could be camouflaged by rebranding them as antidepressants. No-one then thought antidepressants caused dependence.

An added advantage was that unlike anxiety, everyone at this point bought into the idea there was a lesion, a defect, in depression, which antidepressants correct, cure, remedy but it takes time. They don’t sap our moral fiber by providing some early onset tranquilizer type crutch.

Even though both noradrenaline and serotonin inhibitors could now treat depression, even if weakly, Sulser’s Receptor Hypothesis survived. It transitioned from being a Catecholamine Receptor to a Final Common Pathway Receptor.

We held onto the idea of a chunk of moody protein that treatment took a few weeks to chisel back into the right shape. But this Grin now got in the way of seeing the Cat – the immediate onset benefit SSRIs can produce

The weak antidepressant effects of SSRIs made it difficult to show they worked in the conventional antidepressant trial format. Clomipramine and imipramine walloped them in trials of severely depressed patients. In mild depression trials, SSRIs struggled to beat placebo at the 6 week point which was needed to get a license.

But beat placebo they did in roughly half the trials done and companies got licenses to claim SSRIs are antidepressants. Whence came the idea you must keep taking an antidepressant for up to 6 weeks – it used to be 2 weeks for tricyclics – even if you are having a disastrous short-term effect.

Companies could have run one week trials of their SSRI against placebo showing that 50% of us get an almost immediate serenic effect which placebo takers don’t get. Critics of the drugs, like Joanna Moncrieff, would not then have been able to say the effects are all placebo based or in the mind. It would have been clear what the drugs do.

But clarity about what their drugs does not necessarily suit company marketing. Instead, doctors were sold the line that nothing useful was happening in the short-term. There was no challenge to the old idea that antidepressants don’t do much for weeks until some chunk of receptor started behaving itself.

In time, in marketing hands, the chunk of moody receptor protein transitioned into a chemical imbalance.

The problem with this idea is in mild depressions, natural recovery kicks in by 6 weeks even on placebo.

The best way to interpret the trial data is that some of us – no more than 50% of us – get a serenic benefit early on – within a day or two. Family and friends can often spot this. This can settle us down, leave us bothering a little bit less, until natural recovery kicks in.

If you aren’t more serenic after 48-72 hours you need to get off SSRIs/SNRIs. It is possible to damp down the agitation you may be feeling with a benzodiazepine or beta-blocker or other drug – this is what companies did in their trials – and you may limp through to 6 weeks and even appear to recover but this recovering will not be brought about by the SSRI/SNRI.

You may appear to be better and be advised to remain on treatment but you will be unstable and all it might take to trigger severe suicidality may be a tweak of the dose – up or down.

So how did I contribute to this confusion?

The first edition of Psychiatric Drugs Explained came out in 1993. Depression was still rare and SSRIs not much used. It offered the standard narrative about antidepressants. Rather than do something useful, they correct a problem and this takes time, which we think has something to do with a final common pathway rather than low transmitter levels.

When revising PDE later it wasn’t absolutely clear this bit needed changing and later editions continued to take this line – with a nuance. As ever milder conditions were being diagnosed as depression and treated with SSRIs, there was an emphasis on the data that these conditions recovered naturally in a few weeks. There was also a new emphasis on evidence that those of us who recover without meds or therapy are more resilient in the longer run.

Therapeutic Principles

In mitigation, I also argued in a 1997 article that rather than being Magic Bullets, it was looking like serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors offered different Therapeutic Principles. Some like noradrenergic drugs could be energy and vigilance enhancing, while serotonergic drugs were more serenic or anxiolytic.

The reason tricyclic are more potent that SSRIs or pure noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors is that they embody a number of beneficial effects. They can enhance energy, make serene, as well as sedate by acting on histamine along with being mildly euphoriant through their anticholinergic effect.

I repeated this point in a 1998 article responding to Joanna Moncrieff and Simon Wessely (writing together) claiming the effects of antidepressants (SSRIs) were in the mind. I don’t think either of them understood it.

I got the idea of Therapeutic Principles from Arvid Carlsson. For more on Therapeutic Principles and why it makes sense to illustrate the point with a slide on Constipation and Laxatives see Madness, Normality and Antidepressant Dysregulation – at Slide 45.

Retrospectively, it is easy to see that the times needed a few unambiguous statements.

- SSRIs are serenic. If this effect is not clear early on, you should stop the treatment and change to something else – as Arvid Carlsson showed even nicotine might be better than an SSRI if it is not making you serenic almost immediately.

- Because they are serenic for some of us SSRIs, if they suit us, can be helpful across a range of nervous states we now call depression but are better called anxiety states – many of which recover naturally in a few weeks.

- Much lower doses of SSRIs should have been available from the start – some people might have done best on doses between 1-5 mg of fluoxetine, paroxetine or citalopram.

- Nobody should ever have been put on doses more that 20 mg of the above 3 drugs or their equivalent for other SSRI or SNRI drugs. There is no point – 20 mg is the top of the dose range – things can only go wrong.

- SSRIs are ineffective for severe depression (melancholia).

- Tertiary Amine Tricyclic Antidepressants (clomipramine, amitriptyline and imipramine) are more effective for melancholia than SSRIs. These TCAs can do useful but subtle things in the short term and typically bring about a notable change within two weeks – although melancholia can also recover naturally in 5-6 months.

Claims that SSRIs don’t work, or their effects are all in the mind are wrong and almost as bad as the idea that someone should persist with treatment even if getting worse. SSRIs clearly do useful things for some people that are real enough and physical enough for family and friends to spot.

Many of those who are helped should probably not persist with treatment beyond a few weeks. Some folk who are more introverted and prone to rumination may benefit from longer periods on treatment, but they need to be aware that long-term treatment risks compromising health and even shortening lives.

Suicide Warnings

Louis Appleby, Britain’s Suicide Czar, and others linked to National Suicide Prevention Programs in the US, Europe and elsewhere skirt around the risks of antidepressant induced suicide – See An Appleby a Day Does Not Keep Suicide Away.

As with the role of antidepressants in chiseling away at a bit of moody receptor protein, outlined above, there is a background here that perhaps contributes to a policy dictated approach that is doing more harm than good.

Aspirin and Tylenol (paracetamol/acetaminophen) have been and likely still are among the commonest drugs implicated in overdose deaths, intentional or accidental. For decades, the companies making them successfully campaigned against suicide warnings. The argument was that letting people know you could kill yourself with these drugs would increase rather than lower deaths by overdose. Warnings might kill more people than they saved. It took a long time to get warnings in place.

The same factors likely applied to the original tricyclic antidepressants, some but not all of which can be lethal in overdose. There is a twist to this story. The SSRIs when they came on the market were sold as safe in overdose compared with those dangerous tricyclic drugs. although this is not entirely true. Companies were dishing out backhanded warnings – the labels of the older drugs didn’t tell you an overdose of tricyclics could kill you, but companies made absolutely sure every doctor got the message.

We now avoid mentioning overdose deaths or suicide in drug labels if we can.

The SSRIs trigger suicide problem has been buried in our ‘traditional approach’ to this tricky issue. The problem with the traditional approach in this case is that no-one is accusing SSRIs of being dangerous in overdose. The problem that they and antipsychotics pose is that they are vastly more likely to trigger suicidal (and homicidal) behavior than anything else out there – including stimulants, cocaine, opioids and all other prescription drugs.

We are increasing not decreasing suicide rates by failing to warn about this.

Suicide and Withdrawal

Faced with their golden geese laying suicidal events in their SSRI trials, companies took suicidal events from the run-in phase of their trials – where people had been whipped off prior treatment with an antidepressant – and moved these events into the trial placebo column.

This breached regulations and should not have been done. In so far as it could not have been done by accident – all companies could not accidentally have had the same ‘accident’ – it looks like fraud and FDA have tacitly conceded this.

If you can call it a silver lining, the silver lining in this case is that it drew attention to – or could have drawn attention to – the consequences of whipping people off prior treatments. Abruptly stopping causes suicidal events – perhaps even more so than at any other point in treatment exposure. This became clear in company healthy volunteer trials also – most notably with the death of Traci Johnston.

Study 329 is famous for showing a huge gap between the rate of paroxetine suicidal events compared to placebo. GSK never published the continuation phase of this trial which showed the Taper phase to be the riskiest phase of all. Study 329 Continuation.

Their healthy volunteer trials enabled companies to design their trials to hide the problem of withdrawal – any anxiety, depressive or suicidal symptoms were viewed as relapse of the original condition rather than withdrawal symptoms that had also occurred in healthy volunteers.

This applied to supposedly independent studies like the Antler or Kendrick studies also. Because the teams behind these studies don’t have access to prior healthy volunteer data they assume that anxiety, depressive and suicidal symptoms in patients withdrawal are evidence of relapse.

In addition, there is a regular stream of comments in response to articles in lay media on antidepressants and withdrawal hazards claiming that these drugs have saved the life of the person commenting – which they probably have but by treating a withdrawal issue rather than a mood disorder.

Amidst all the noise, it is difficult to detect the voice of anyone who knows anything about pharmacology or how clinical trials operate or can be made to operate. The best the critics seem able to do is squirt the octopus ink of ‘conflict of interest’.

Footnote

When the SSRIs became more than a glimmer in Arvid Carlsson’s eye, Lilly who had been developing nisoxetine and later atomoxetine pivoted to fluoxetine.

In the 1994 Wesbecker lawsuit, John Heiligenstein, one of Lilly’s honchoes when interviewed under oath seemed to have a terrible memory of the details of fluoxetine’s development. He said yes he had, this was because he had Adult ADHD. How did he know this – well he said he had found atomoxetine helpful for it.

Based, it seems, on his experience or whatever. Lilly were then in the process of bringing atomoxetine on the market not as an antidepressant but as Strattera. a treatment for ADHD, and their marketing department had a wonderful idea – they needed to persuade people that ADHD was not something you grew out of – you had it for life.

Since then millions of adults have developed ADHD – who never had it in childhood.

When I was a boy, “hyperactivity” was a hotly contested diagnostic category applied almost exclusively to elementary-school-age boys who were fully expected to grow out of it. Today, “ADHD” is a crippling, life-long disorder responsible for just about every human woe, and one that requires cradle-to-grave drug treatment.

Thank you for another masterclass in psychopharmacology.

Six ‘Unambiguous Statements’.

Today in England; mainstream media platforms are reporting the new recruitment of 1500 additional General Practitioners.

If only these new GPs (who will have completed three years post-registration – Vocational Training in General Practice), – were given the opportunity to have been taught these six vital, safe prescribing statements, and

to fully understand the pharmacology underpinning their validity and importance.

How much Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) induced psychiatric misdiagnosis, unnecessary psychotropic

poly-pharmacy, false imprisonment, iatrogenic maiming, life changing injuries and AKATHISIA related deaths might be avoided?

How many devastated families might still be experiencing the day to day joy bought to them by their adult children, had their young lives not been destroyed by irreversible prescription drug induced injury?

How many lives and families have been destroyed by mainstream psychiatry’s denial of these six unambiguous statements and by their Misdiagnosis of Psychotropic ADRs as ‘Serious Mental Illness”.?

Labels for life, resulting in societal rejection and the dangerous, lifelong medical assumption that subsequent physical ill health MUST BE a manifestation of their previous (none-existent) ‘Mental Illness.

They immediately recognise this subsequent medical rejection. It is palpable, hurtful and dangerous.

Here, in these Unambiguous Statements lies a great Preventive Medicine/Public Health opportunity sought by our Secretary of State for Health.

To save our NHS, surely the Critical Success Factor is to recognise and call to account The NHS’s greatest failure?

I’ve got the seventh edition of ‘Psychiatric Drugs Explained ‘ – and you do acquit yourself for not trashing the 6 week delayed benefit claim, by emphasising several times:

‘the first effects of antidepressants, good or bad . are likely to be visible within days rather than weeks’

‘it does take several weeks to break up a depression but benefits willmoften be apparent within 1-2 days if looked for. This may range from the tonic effects of some TCAs..to the anxiolytic or serenic effects, to drive enhancing effects of noradrenergic drugs. This is more obvious when these drugs are given to healthy volunteers..’

I was particularly taken with this insight – ‘the greatest block to recovery may often be the person’s own idea of what it means to be well – ‘treatment should make me into someone who never has any ups and downs again.’.

When discussing the awful, predictable, drug induced, or at least not drug prevented, suicide of my twitter friend, R – you asked, how can we stop the lunacy – (with an unspoken – which appears to be getting worse). I’m sad to say that I kind of agree with you re the getting worse. I used to feel more optimistic.

Yes, there is a theoretical acknowledgment that ADs cause withdrawal, even severe in some patients, that PSSD, akathisia, suicide are real risks –though diminished by vested interests in terms of assumed rarity – rather than properly explained in terms of a risk to everyone who swallows an SSRI. There is a token nod to social prescribing.

But, what makes me fearful of the ongoing lunacy is the young. So many have internalised the sales patter of mental health –‘ my depression’, ‘my anxiety, ‘my BPD’, ‘my ADHD’, ‘my autism’, ‘my chemical imbalance’ – it’s a way of life, it’s an identity, it’s effectively a contemporary fashion statement.

I went for a cruise around tiktok earlier looking for ‘BPD’ posts – and what I found was shocking. Mostly young women ofc – not only swallowing the nonsense, but positively embracing it. For example, take young Brooke here – and I recommend taking several calming breaths before viewing:

https://www.tiktok.com/@brookejamesxx/video/7297329161264287008?lang=en

And, moving onto ADs, this young woman despairing of the chemical imbalance in her brain that needs medication:

https://www.tiktok.com/@user1837392739274/video/7466167336601521441

One smart guy had read the research and knows the serotonin deficit theory is rubbish, but sees it as a social control conspiracy. Maybe closer to the truth.

https://www.tiktok.com/@dravonishereagain/video/7384180177011625259

It always seems to come back to the need to win the information war – you’ve been fighting for years – with harmed patients. The six unambiguous statements crack it . Clarity shouldn’t be so impossible should it – especially when companies have their sights trained on other blockbusters?

It’s certainly going to take more than Wes being mean about disability payments for people with ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’, and RFKJr flashing his pecs re FDA integrity to turn this medicalised tanker. Maybe there will be a generational backlash? Assuming SSRIs and microplastics don;t scupper that option.

Moral of the story – for a positive outlook – avoid late night tiktoxicty.

Dr. Healy’s article, “Six Weeks to Recover a Grin,” offers a critical examination of the longstanding belief that antidepressants require six weeks to take effect. He argues that this notion may lead to dangerous delays in addressing adverse reactions, such as increased agitation or suicidality, in patients who have recently started these medications. By tracing the historical development of antidepressants and highlighting the immediate anxiolytic effects observed in some cases, Dr. Healy challenges the conventional timeline for therapeutic response. This piece underscores the importance of individualized patient care and the need for clinicians to remain vigilant for early signs of adverse effects, rather than adhering strictly to generalized treatment timelines.

I’m a retired hospital doctor (paediatric anaesthesia and intensive care) and new to commenting here. Our daughter took her life at 29 nearly 2 yrs ago, after a 3 yr saga of SSRI/SNRI prescriptions, difficult withdrawal and dose increments for recurrent symptoms. In the aftermath, no-one involved in general practice or mental health engaged with the idea that persisting with antidepressants in the face of intermittent akasthesia like side effects led to her demise. I eventually found RxISK and reported her story, sadly so similar to many others.

The tragedy is that she was instinctively reluctant to start SSRIs in March 2020 but did so because she feared that the looming Covid restrictions would curtail most of her usual coping mechanisms for anxiety – sport, social life, etc. There was plenty to be anxious about at the time. I don’t think she had a significant depressive illness, but, like many of her peers, she worried about her mental health.

I believe that if she had been given appropriate warnings (and accurate numerical estimates) about the risks of taking SSRIs, specifically sexual dysfunction, suicidal ideation and the prospect of difficult withdrawal, she would not have started them and still be with us.

The problem starts in general practice, so often fragmented, discontinuous and difficult to access for follow up. Ironically, I think their workload would be significantly reduced by adopting a much higher bar for initiating psychotropic drugs and abandoning the 6 week persistence mentality described in David’s post.

If you react badly, stop the drug and don’t keep trying others in the same class. Secondly, involve the family early unless the patient declines, preferably before giving any pescriptions for which there is no urgency. Many families would cope admirably, given the right information. Most older folk are skeptical about over medicalizing Gen Z’s anxiety “epidemic”.

How might any of us influence practicing doctors and their trainees? My attempts at direct feedback over the last 18 months have been frustrating, to say the least. Yesterday, I found this NHS England consultation exercise. I have no idea whether my submission will have much, if any, impact but it is worth a shot if you have a couple of hours to spare and can get past the jargon. You can also submit further “evidence” to their email address.

NHS England (still functional, apparently) Medical Training Review process open to submissions up to May 2oth.

https://www.engage.england.nhs.uk/survey/medical-education-programme-review/

Finally, GPs and patients have shared decision tools from NHS England available to them to encourage asking the right questions, using the acronym BRAN – Benefits, Risks, Alternatives, do Nothing (watchful waiting). Much as it seems like the bleeding obvious, how many consultations actually follow this in practice, especially the A & N?

Richard

This is a powerful and likely painful for you comment – thanks.

I don’t want to trivialize anything but your ending brought an immediate thought to mind – BRAN is up against BRAND (Nothing doing rather than do nothing).

The labels of generic drugs must by law stick to the brand label. Lilly have totally divested themselves of Prozac (and fluoxetine) and GSK are doing the same for Seroxat in the UK at least. It looks like the labels for these SSRIs, and perhaps all other SSRIs as a result, are frozen in time and will be for ever free of the blemish of warnings. Companies write warnings not regulators. So unless Governments intervene and rewrite the rule-book as the British Government is with British Steel today, it is difficult to see how change can be legally brought about.

Family Doctors could step in. They have more power than any other group in society – and work to rule but in this sense – saying they will only prescribe these drugs if there are decent warnings. Doctors, especially Family Doctors are on the only group besides companies who can legally insist on a change like this.

D

Richard

Your daughter’s story is a tragedy. I’m so sorry. The ignorance and /or refusal of her doctors to recognise the contribution drugs and their prescribing decisions made is painfully familiar.

It’s clear from the UK’s Suicide Prevention Strategy that one of the groups where suicide rates are increasing is young women. As you observe, and I totally agree, the ‘anxiety’ epidemic amongst GenZ is a significant exacerbation.

‘While the suicide rate in under-20s is relatively low compared with older age groups, rates across all age groups under 25 have been increasing over the last decade in England. This increase is particularly apparent among females under 25. ‘

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-strategy-for-england-2023-to-2028/suicide-prevention-in-england-5-year-cross-sector-strategy

The problem isn’t only doctors, GPs especially, having little or no idea of the risks of antidepressant prescribing – no coherent notion of the 6 clear points that David makes in this blog – but patients also demanding ‘antidepressants’, because they believe the commercial mythology that these alarmingly ubiquitous drugs are ‘safe and effective.’

As far as I know (as a layperson working p/t on drug safety in the NHS), unless the MHRA issues a mandatory – as they have with valproate for a signed ARAF (annual risk assessment form) and the use of decision aids, after 20 years and 20,000 patient/families affected by teratogenesis – guidance and decision aids are no more than optional. Which is outrageous when they could save a life, like your daughter’s – and, as you say, so many others.

David is the best person to guide you on the most effective courses of action. But one thing you could do is write to the Chief Safety Officer at the MHRA, Alison Cave, copying in the Patient Safety Commissioner, Henrietta Hughes, adding your medical voice to the work they are doing currently on the safety of antidepressant communications vis-à-vis suicide risks and enduring sexual dysfunction.

Antidepressant induced suicide, inadequately addressed for years, needs escalation to the political level to force any significant action. So perhaps involve your own MP if they’re engaged. Esther McVey is another politician to connect with – she has spoken out about these issues in parliament and specifically the suicide of her constituent, Olivia Russell, during SSRI withdrawal. It is obviously more powerful if bereaved families work together to campaign rather than individually.

https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2024-11-26/debates/24112677000001/SuicideAndMentalHealthOfYoungPeopleTatton

David knows this drug safety space better than anyone – and of course he’s right about the potential power of GPs as a group to do the right thing. Why they don’t is a mystery to me. Relying on outdated training? Too busy to think? Too passive to act?

The outcomes are tragic – and mostly avoidable. As you know too well.

Harriet

Harriet

Thank you. I hope to keep chipping away and will contact MRHA & politicians. One of my retired GP friends has also offered to help me with an article for one of their journals.

On a statistical basis, most GPs won’t encounter an AD related suicide in any particular year, or even in their entire careers. Probably more often than not, such an event still will not be recognised as such. I imagine most families, like us, are reluctant to push for a publicised inquest, with legal representation, expert witnesses, etc..

On the other hand, sexual dysfunction and withdrawal symptoms must be on their radar even if some patients are prone to understatement.

This weekend, the Times had a tongue in cheek editorial about the increasing use of AD drugs, e.g. fluoxetine, in dogs – “Owners who opt to ply their pooches with pills are surely being sold a pup”…..

Experienced dog owners would recommend a couple of hours trotting and sniffing round the woods, or a trip to the beach, for sad housebound dogs.. Perhaps there is a moral here for humans and their GPs.

Some of the enthusiasm for social prescribing and lifestyle medicine, although patchy, is encouraging.- see ~47.00…,54.00… for approaches to depression in the video below.

If you already know what works for you and have the resources, perhaps you may just need to be told you don’t need a pill.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-R5ihIvJ0A

If Tiktok videos are depressing you, perhaps try one of our daughter’s stand up snippets. I didn’t know what tiktok was until she told me this one went viral.

https://www.tiktok.com/@josarginson/video/7194054912425069829?lang=en

Richard

Harriet

Thank You

I have seen a video of the Westminster Hall debate involving Ester McVey and Steven Kinnock. Notably, the chamber was almost empty and only a couple of other MPs spoke…

Also the debate in the HoL (11/12/2024), initiated by a question from David Alton, which was a bit more lively but only lasted 10 min, before moving on to special needs education.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ZyDD86KAeE&t=15s

This was accessed through David Alton’s website but it has only been viewed 36 times in 3 months on the “Worth Watching” YT channel.

The emphasis in ministerial replies is always on the need for more MH services, with better access. However, the philosophy of such services is crucial. Our experiences resonate with the problems described in a paper by Chloe Beale, a liaison psychiatrist in London, who I heard, by chance, speaking on a radio 4 program.

“Magical thinking and moral injury: exclusion culture in psychiatry.”

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8914811/pdf/S2056469421000863a.pdf

Of course, one shouldn’t generalize and I’m sure there are pockets of better practice. The problem is finding and accessing them.

I will contact the politicians and MHRA as you suggest. I’m no expert in this field and they need the advice of David, yourself and RxISK colleagues. Hopefully hearing more voices may help to promote a full parliamentary debate and more decisive MHRA action,

Richard

Richard

I’ve just watched my first two instalments of Jo’s tiktok videos – and literally laughed till I cried. The one you posted – and dating with a nut allergy – aka ‘being dumped for a chocolate spread’. Brilliantly funny and original ideas. Brilliant comic timing and delivery. What a vibrant, gorgeous human being.

I think you’re absolutely right that most GPs won’t encounter – or more likely won’t know they’ve encountered (or worst case will be given legal advice not to know they’ve encountered) – antidepressant induced suicide. Patient reports – and they know best, they’re the ones experiencing the adverse drug effects – show that the default professional setting tends to be the patient is having a mental health problem, not the drug is having a toxic effect.

One of the PSSD community, a particularly poised and articulate young woman called Emily Grey (whom David ofc knows) gave such a brilliant interview the other day. She invoked the concept of DISENFRANCHISED GRIEF to explain the psychologically abandoned state of so many patients whose experiences are disbelieved and invalidated by the system:

‘Disenfranchised grief is a term in grief psychology when somebody experiences a loss not recognised by the society around them. It compounds the grief & delays the healing process because they don’t find understanding within their community or within their families’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hZ3U0lk

It’s great to hear that you, with your medical authority, (in my experience of life – anaesthetists and pharmacologists are the only ones who you can trust to know about drugs) are tackling politicians and regulators about drug safety. David is a world expert in iatrogenesis, best placed to advise. I’m just a highly motivated neophyte – always happy to try and help. Please just ask.

I wonder what you find – as a proper specialist doctor… Over the last 4.5 years of layperson involvement with the NHS – I find that everyone within the system firmly believes they prioritise patient safety. Fair enough with major high risk surgical interventions – your sphere of work I imagine.

But for ‘everyday’ medicine, especially drugs, the system seems to assume patient safety (based on corrupted evidence) but doesn’t actively practice it much. There’s a sort of vigilance burnout. I suppose for GPs seeing on average 37 patients a day it’s not surprising. It’s like they’re automatons.

As the owner of a beloved 10.5 year old German Shepherd, who has only ever been given a cat’s dose of Metacam about one day a year when he injures himself running over fields and hobbles (or I do occasionally), I share your disgust with pharmaceutical companies pushing psychotropics on dogs..I expect there’s a market for hamsters too.

Harriett

I’m retired and had hoped to spend most of my time catching up on interests which had been relegated to the back burner during working life.

Retired doctors, despite their experience, generally find themselves largely ignored by their successors, regulators, etc, We might see each other at retirement dinners, funerals and the occasional lunch and exchange a few wry observations on the current state of affairs.

A motto often quoted in anaesthetic and ICU circles is “Eternal vigilance is the price of safety”. When you are using combinations of potentially lethal drugs (with narrow theraputic margins) and the patient becomes entirely dependent on you for supporting their vital functions, safety is a dominant issue.

This is re-inforced by critical incident meetings, confidential enquiries (e.g. NCEPOD), medical defence organisation reports, the coroners court and a specialist literature which includes case reports of adverse events, technical malfunctions & other hazards.

Outpatient medicine is very different. The impact of taking a prescribed pill or combination is generally not directly observed and the onus is put on the patient to report back. This has often become more diifficult in recent years as care has become more fragmented and barriers to appointments can be challenging to navigate.

If you happen to be in a study or trial, perhaps you will be more closely observed. You could argue that some treatments are effectively “n of 1” trials, eg. when ADs are ontinued past the duration of any prior reported study.

Many patients may struggle to get due vigilance from the individual prescriber. if adverse effects do occur. That may or may not be a good thing, depending on the experience, knowledge and attitudes of whoever you get to see or talk to in general practice, A&E, or suicide help lines, etc. Also, as doctors have generally become more specialized, whether you can get to see the best person for your problem locally can be very hit and miss.

In a review after Joanne’s final illness, the mental health trust noted that her care had been passed on 6 times (between GPs and CMHTs) without “further advice on prescribing being addressed”. Also that the two CMHT teams who assessed her once each did not have direct access to staff “with medication prescribing skills..” That we only discovered this after the inquest almost beggars belief.

We have been reluctant to go public with Joanne’s story. She would probably not have wanted too many details of her life or death in the public domain. However, she put some of her humour out there over several years, even occasionally alluding to mental health struggles…Comedy was only one of her talents and she had several other strings to her bow.

https://joannesarginson.com/2023/05/30/mentalhealth/

No 4 is a good argument for including a close family member or friend in consultations. We will never know if she understood how the “existential hole” might have been influenced by antidepressants..

My view is that the key issue is not to prescribe these drugs in the first place, without proper informed consent, considering alternatives, a clear understanding of the risks and involving close family, unless the patient declines.

Protecting confidentiality is a dangerous game if treatment can result in loss of capacity or irrational behaviour in someone not previously prone to such things.

An analogy would be that starting ADs is often like putting someone in a canoe in a calm stretch of water, but not warning about the rapids downstream, the risk of capsize or that sections of the river lack rescuers.. Once adrift, it may prove difficult later to reach a safe shore, even if most people have somehow managed it in the past..Your guides, if you have them, may abandon or lose you, or a storm surge might blow up…..Even though you may want to come ashore, you might be advised to push on because sunny uplands await you downstream if only you persevere…..

Probably better to continue the more personal aspects of the conversation on email.

Richard

I am sorry to reply so late to your deeply moving comment Richard.

Thank you for joining those of us who find support, information and comfort from D.H. Blog.

Some of us, like yourself are doctors who have been betrayed by unneeded psychiatry.

Our loved ones, and their families have suffered greatly, and avoidably as a result of (often unnecessary) psychotropic drugs, prescribed without fair, full and informed consent.

Your brave and heartbreaking text is analogous to many of our appalling experiences of a drug dominated psychiatry which is more Cult than Medical Speciality.

Close links between the RCPsych and RCGP go back to the ‘Defeat Depression’ Campaign of the 1990’s which left the continuing legacy of overprescription of ‘antidepressants’ without adequate information on the potential life-changing and life-ending adverse reactions.

Although I initially trained in General Practice, I spent my working life as a consultant physician.

We always held great respect for the pharmacological knowledge, and the skill of our anaesthetist colleagues.

For 14 years,I have tried to increase prescriber awareness of the adverse drug reactions that destroyed our loved ones: with particular emphasis on AKATHISIA, SUICIDAL IDEATION and PSSD.

How many of those misdiagnosed as “Serious Mental Illness” were suffering entirely from iatrogenic, psychotropic adverse drug reactions.

ADRs unrecognised both by GPs, and by psychiatrists?

How long will sincere, caring, real doctors continue to tolerate this tsunami of iatrogenesis?