Drug companies use studies the way a drunk uses a lamppost — for support rather than illumination.

This quote adapted from English romcom author Jilly Cooper (who adapted it from others before her) seems an appropriate preface for a series of company approaches to data handling that have concealed rather than revealed treatment-induced problems.

In another galaxy, far, far away, somewhere in 1986, staff at Eli Lilly compiled the data on suicides and suicidal acts from Prozac clinical trials for reports they had to submit to regulators in the US, Britain, Germany, and elsewhere. They compared events on Prozac to events on other treatments, including placebo, no drug, or older drugs. In trials conducted in the US, they listed 4 suicides on Prozac and 1 on placebo, along with 26 suicide attempts on Prozac versus 9 on other. Various reports of this type were compiled and submitted to the regulators over the following four years, and part of the data ultimately ended up in a BMJ article published in 1991, at the height of the Prozac-suicide controversy, during the week FDA held hearings on antidepressants and suicide.

The 1986 data are intriguing. A short account of each suicide and suicide attempt is laid out. In the case of Prozac, 7 are discounted as not genuine suicide attempts; none on placebo are discounted this way. Of the 9 attempts classified as placebo or other, 4 involved patients treated with fluoxetine who had relatively recently discontinued from it. Classifying these under the heading of placebo, even in 1986, looks unsupportable.

Of the 4 suicides on Prozac, 3 are listed as using it under compassionate-use protocols, and these patients had been on it or exposed to it over a 3-4 year period. At first sight this doesn’t make sense; why include 3 extra suicides in the Prozac column? These suicides don’t find their way into the later BMJ article, for instance, where the company might have expected reviewers to ask for them to be removed. The 3-4 year period is key; this allows the company to make the case to the regulator that when the duration of exposure to Prozac is taken into account, the rate of suicides and suicidal acts is no greater than on placebo.

Method for counting adverse events

As of 1986, the standard method mandated by regulators like FDA for counting adverse events was to count events in proportion to the number of people exposed to the drug rather than events in proportion to the duration of exposure.

Insisting that events be counted in terms of duration of exposure is a way to make travel in space shuttles safe. If crashes are counted by the number of trips the shuttle takes, then it is about as risky a mode of travel as you can find. If crashes are counted by the number of thousands of miles travelled, it becomes maybe even the safest form of travel. The key thing with the space shuttle is that the risk periods are entry to and exit from orbit. For many (but not all) drug side effects, the riskiest periods are also entry into treatment and exit from it.

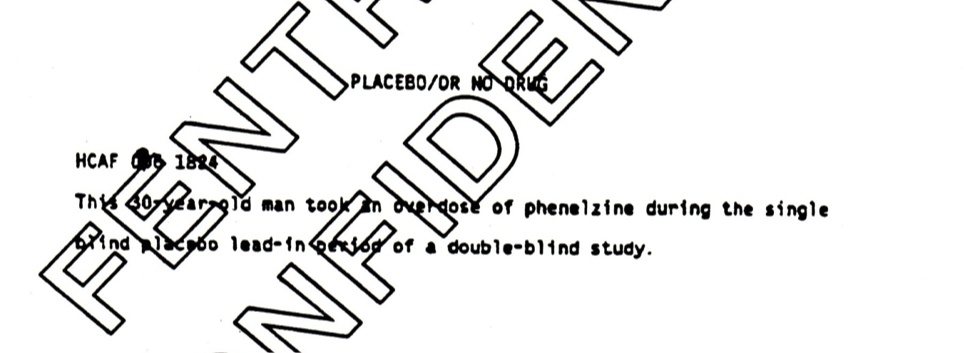

The placebo suicide

The most interesting event is the placebo suicide. This happened during the lead-in phase of the trial, when a patient removed from his prior medication during the week before starting in the trial proper committed suicide. A placebo suicide remains in the analysis all the way through to the later BMJ article — still coded as happening during what is variously called the lead-in or wash-out phase of the trial. See Figure 1.

Figure 1

At the time, the regulations for submitting data to FDA made it clear that this should not happen. It was inappropriate. A later reviewer of an article I wrote on the issue wondered if it was outright fraud. More than 12 years later, when they again called for data on the antidepressants and suicide, the regulators made it clear to companies that they should not do this.

But there has been no public acknowledgement that this was done. No detailing of who turned a blind eye to the issue. How do we account for the fact that a series of regulators across Europe and North America appear to have turned a blind eye at the same time? Why when the issue is in the public domain do the legal departments of major academic journals like BMJ or NEJM advise journals not to carry articles mentioning the issue?

When the range of ways the suicide data were handled by Eli Lilly in this case or other companies in other cases do come up, companies tend to portray themselves as not statistically sophisticated. The implication is that if things went wrong, they did so by accident. The response from regulators and others has often been that perhaps mistakes were made but this is now in the past. There is no need to take an adversarial approach with companies, we are told, we don’t expect this to happen again.

Don’t we?

The January 6th issue 2011 of the BMJ – the journal which carried the original article in which the Ghost suicide first appears – was devoted to the issue of academic and research fraud and the need for access to the data from trials. There was lots of mention of Andrew Wakefield and his MMR study but none of this or any other comparable distortions of the data by pharmaceutical companies.

We expect academics to do this again but not pharmaceutical companies?

As the BMJ issue could have shown, this is not something from a distant galaxy long long ago – almost identical strategies were adopted by Pfizer and SmithKline Beecham for Paxil and Zoloft in the 1990s, and then by Merck for Vioxx and GSK for Avandia in the 2000s.

These methods hid a crucial few deaths on each drug, but as we shall see in the next post, there are even better methods to hide many more deaths.

Where do pharmaceutical companies look for data and/or direct a search? I’m reminded of the following:

It’s a dark night. A man walking home sees someone on his hands and knees crawling around under a lamppost. He stops and asks the man what he’s doing. “I’m looking for my wallet,” is the reply.

“Where did you drop it?” asks the first man.

“Over there” says Hands-and-Knees pointing off into the shadows.

“Why are you looking here, then?” asks the first man.

“Because this is where the light is, of course.”